|

|

|

'How can I improve my practice as a superintendent of schools and create my own living educational theory?': Jackie Delong

|

Chapter Four: Creating my embodied knowing In being a leader

Chapter Four connects my learning from experience, the creation of my embodied knowing as a leader, my integration of ideas from the literature on leadership and my support for individuals to develop their capacities as I discover and manage resources to support visions of an improved educational system. I conclude by emphasizing the importance of my knowledge-creation in my professional practice as a Superintendent of Schools and by asking and answering the question: Why is there no simple or even complex answer to "what is educational leadership?"

In the rhythm of the work, my efforts are often full of risk, sometimes disastrous, at which point I fall back, renew my energy and with my recognized tenacity, try another route. I will reveal as well how I carry that spirit, that life-affirming energy (Bataille, 1962; Whitehead, 1999) embodied in my whole being with a passion and internal power to effect good. Feminist Barbara Du Bois (1983) writes of "passionate scholarship" as being "science-making, which is rooted in, animated by and expressive of our values" (p. 113) (Belenky, et. al., 1986, p. 141). One of the reasons I can accomplish as much as I do is that the work and the relationships appear to be many and complex but because they are inter-related and connected they provide a synergy that produces results in numbers of seemingly different and unrelated focus areas.

I find that as I am supporting individuals like Cheryl and Greg 1

and Maria 2

and Kim 3

in dialectical and dialogical processes that I am learning and improving myself and at the same time educating social formations (Bourdieu, 1990). I hold onto a vision of a whole system dedicated to the learning of everyone in the organization, but most especially the learning of the students. That vision is wrapped up in an ethic of inquiry, reflection and scholarship, of valuing the other in a relational leadership as I create my living educational theory (Whitehead, 1989, 1993, 1999). Working at a systems level is a study in the complexity of cultures and historical relationships and a test of political nous to tap and enhance its resources and influence the way the organization works.

I begin with a narrative of my relationship with one of my staff, in this case a non-educator, Maria, Training and Development Officer who worked with me in staff development which includes leadership development programs.

|

|

|

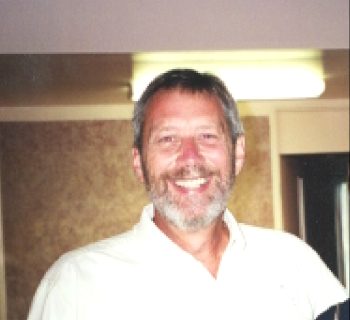

Maria Birkett, Training & Development Officer, 1998-2002. I have know Maria for over three years.

|

|

Working with Maria

When I think of leadership, I think of the people that I work with and the ways in which I encourage and support them and what they have taught me. To share my experience in staff development I must share an image of Maria Birkett so much a part of my doing and learning and caring.

As I wrote in her performance evaluation, it has been one of the purest pleasures of my career to support and encourage Maria Birkett's career development (Delong, 2000a). When the decision was made by Executive Council to hire a Training and Development Officer who would not be a teacher, I had reservations. I argued that it needed to be a teacher to have the respect of the staff and to have the capacity to do the job. I was wrong on both counts. As part of a team who interviewed and offered Maria, a human resources secretary, the job, I was very clear on the expectations as I wanted her to fully understand that it would be a challenge. She looked me straight in the eye and said she would give it her best shot. What a lucky day for me! From day one, she poured herself into the job, asking questions, investigating possibilities, taking initiative, and building relationships. She has superior interpersonal and organizational skills. I remember her saying in the interview that the one part of the job she could not do was to conduct workshops. We laugh frequently about that because within six months she was doing them as a partner with another staff member and after a year in the job was doing them frequently without taking much notice. Here again this recurring theme of my having faith in the other and their willingness to attempt what they thought was beyond their capacities with my support and finding abilities they didn't know they had.

One of the areas that we focused on in her role was staff development for the non-teaching groups in the board, an area that had been neglected in the former boards. These included secretaries, non-union managers and educational assistants. Maria's background and connections were invaluable in this work. She managed entire Professional Development Days, Volunteer Development and Summer Institutes programs creatively and competently. The other area of her work was support for leadership programs. Because of the severe shortage of school administrator candidates (Carter, 2001), a provincial problem caused by large-scale retirements and lack of interest in the job, this was top priority work for me. Each of the leadership programs had a program committee but Maria was their support system. Supports included web site connections, committee meeting arrangements, program locations and advertising, conference planning and constant problem-solving. The only time I saw her upset was when someone expected her to do secretarial work. She is calm, caring, competent and her eyes laugh with joy. In April, 2001, she left on maternity leave for a year. I miss her but thinking about her always makes me smile. What I learned in supporting Maria I used to support the interim Training and Development Officer and I look forward with anticipation for her return in April, 2002.

Staff Development and Leadership Programs

Now back to leadership and staff development. I have a long history of experience in professional/staff development including a provincial award from the Ontario Secondary School Teachers' Federation (OSSTF) in 1988. While I have read about staff development (DuFour, 1991; Sparks & Hirsh, 1997), much of my knowing is experience-based and embodied. Putting my life into discrete compartments such as 'Leadership Programs' for the purpose of this thesis is not easily done. However, I do recognize that part of my role as a superintendent is to compartmentalize for the purpose of particular tasks. And thus, when the board requires a report on leadership programs, I am able to make that report in the form and timelines expected (Delong & Moffatt, 2001b). When I presented the new Staff Development Model 4

made the relationships and connections amongst staff development and leadership and inquiry, reflection and scholarship evident to the trustees of the board. The Staff Development Model4, developed in 2000-2001 by a team of educators and non-educators, articulates the assumptions and guiding principles for professional development programs and, as well, incorporates the connections among, and work of, the leadership programs, the action research networks, administrator recruitment processes, and opportunities and means of accessing teacher and non-teaching staff in-service programs.

On July 10, 2001, I conducted a session on staff development with the thirty-two prospective principals on the Ontario Principals Councils' Principals' Qualifications Course (PQP). I realized in the preparation and in the dialogue in the session that this Staff Development Model represented not only my passion for and commitment to professional development but also my belief in involving those affected by decisions (Sarason, 1995). In the session I asked the group to reflect on and share their beliefs and values on professional development. I then shared the ones that the committee had agreed upon as a reflection of the process that had been followed to come up with our board's model, policies and procedures, a process that they could use in a school. One of the candidates on the course remarked that the positions of the committee members were not listed. I asked him what he thought that said about the system. He replied that he felt it showed respect for the individual's contribution and that position didn't matter. I replied that I was happy with that reflection of my system and that it had been Jennifer Faulkner, an Educational Assistant, who had spoken for the committee at the board presentation. If the process is about learning and growth, then every opportunity should be taken to do that.

Part of my regular practice is that I ensure that staff members get the credit for their work and public forums like board meetings provide those occasions. When program or service reviews are conducted, the report is presented by a committee member, often a trustee, and I am the coach (Delong & Moffatt, 1997b; 1999-2001; 2001b) I remember John Moore, Purchasing Agent, remarking at one of the professional development committee meetings when I shared with the group that policies should enable and free staff to do their jobs to the best of their ability that he had never heard policy described that way. And he liked it. This narrative demonstrates my standards of inquiry, reflection and scholarship and valuing the other through democratic and non-hierarchical relationships.

Integrating the Literature On Leadership into My Practice

The values, processes and standards of judgment that I use are embodied in my ontology and evident in my ways of knowing as a leader. When I visualize a preferred future, the faces of the people involved are first and foremost and I am thinking of ways to help them improve what they are doing, not by doing for them but by encouraging and supporting their own questioning and reflection. When I can help others do a better job I am moving the system forward toward an improved version of itself. When I encourage and support leaders in the organization, I am creating sustaining systems and succession planning. Essentially I am doing myself out of a job by supporting their independence and interdependence. Fortunately, there are more jobs than I can do in a day and others for me to move on to. I would like to emphasize the positive influence which some thinkers and researchers have had on me and how aware I am of using their ideas.

The work of Stephen Covey (1989; 1990; Covey et. al, 1994) has been very influential in my working from the inside out, in making relationships and planning 'quadrant two" priorities, in seeking first to understand the other and in listening empathetically. In all the readings on leadership that the Reading Group that Diane Morgan and I initiated and supported from 1995 to 1998, and that Peter Moffatt supported and sometimes attended, no writer has had a greater influence on our system. In the year 2000, this influence was evident in the fact that two principals, Don Backus and Keith Quigg, 5

were trained to conduct workshops on the Seven Habits of Highly Effective People (Covey, 1989), over two hundred staff teachers, administrators, non-educators and School Councils members attended the training workshops. All of these people volunteered for the training. The values and philosophy are becoming part of the culture of the Grand Erie District School Board (Cottingham, 2001). 6

|

|

|

Linda Grant, OCT Manager, responding to my paper, ‘ My Epistemology of the Superintendency’, February 18, 2000 at my Validation Group meeting at the ARR Conference.

|

|

What I've Learned about Leadership in This Role

What I think I've learned about leadership I can share with others but I would be concerned if anyone thought I have a model or prescription to follow. I find leadership to be context specific, dependent on the gestalt and very much a problem solving, creative thinking and relationship-building exercise. In Amanda Sinclair's (1998) work on 'doing leadership differently' there is delightful rhetoric but no evidence that anyone has done leadership differently in her book. The kind of leadership that I believe I am living is based on the living standards which I use and ask others to use in judging my way of leading. I want to note here that I first wrote 'use to develop in others' and remembered Linda Grant's recommendation at the February 2000 Validation meeting that she didn't think I meant that I thought I could 'develop' others. I agree. I believe I can open some doors and offer opportunities but they must have the will and commitment to improve. I include this in order to integrate the methodology of this thesis and my emerging epistemology. I have been learning and developing my expectations and living standards of practice with Peter Moffatt, Director of Education, over many years but researching to improve them over more than six years - 1996-2002. They have evolved in a dialectical development of my own ideas on leadership and engagement with others. I was able to articulate at the Act Reflect Revise Conference IV on February 18, 2000 that I am what I have learned and experienced as a leader. I said that I like to foster the creative capacity in each individual in the same way that I have been supported as a creative thinker and leader by Peter Moffatt. In a process of "creative collaboration", "we have to recognize a new paradigm: not great leaders alone, but great leaders who exist in a fertile relationship with a Great Group" (Bennis & Biederman, 1997, p.3). This is at the heart of how I envisage educational leadership.

In a collaborative process that included dialogue amongst Executive Council, Planning Council and Principals, Peter and I developed some personal characteristics and capacities that we feel capture the nature of the leader that we are looking to appoint in the Grand Erie District School Board. They are not intended as a checklist but a framework which might be helpful in the "Preparation for School Administrator Positions." It began with an introduction:

People who are interested in becoming School Administrators in Grand Erie should seek (and be provided with) opportunities to demonstrate current knowledge, growth and skills in a variety of areas. These leadership skills are developed over time, through experiences. Creativity, enthusiasm, initiative, calculated risk-taking are important traits for School Administrators. Honesty, loyalty, dedication and paper qualifications for the position are assumed. A variety of different educational experiences is desirable to develop perspective (Delong & Moffatt, 2001b).

This introduction was followed by a number of skill areas that might be included in the development of a leader and which applicants to the role use to prepare for the position. 7

These are only lists without the stories that the applicants are asked to include in their applications. Only then do the capacities and skills and values come to life. Also in the process, the supervisor is asked to validate the accuracy of the stories. As with the OCT standards, we wanted to avoid linguistic checklists (Delong & Whitehead,1998).

When I am interviewing prospective leaders or providing Professional Development sessions for aspiring leaders, I have a vision of the leader that I want leading the schools in my system. When I say that I envisage a leader who has the capacity to inspire others through strongly held and lived values of "honesty, fairness, caring, integrity, trustworthiness, and democracy", I am seeing the faces of people like Greg and Cheryl 8

and Kim. 9

A leader who has the ability to create and hold onto a vision for good, attract others to that vision and act to bring it to fruition brings up images of Maria (above) and James and Diane 10

. I support and encourage competencies like the capacity to think, reflect, plan, communicate, problem-solve and challenge "mental models" (Senge, 1990). I hold high expectations but give sustained support and work with and see the strengths of others. Educational leaders who have knowledge of learning and teaching and emphasize the relationships hold a long term commitment to creating a better social order (McNiff, 1992). Leaders, like Ruth Mills and Lynn Abbey 11

, have a joie de vivre, a life-affirming energy (Bataille, 1962; Whitehead, 1999) that is visible and inspirational and a passionate commitment to improvement and career-long professional growth. Their power lies in their capacity to influence, not in their position or position-power. They are collaborative, engaging and productive. They make my task as superintendent a real pleasure and personally and professionally fulfilling.

The leadership programs that I help to design always include 'building relationships', 'planning' and 'program' as topics of sessions. Building relationships starts with knowing oneself and then getting to know others (Not surprising that Greg Buckles and Don Backus were the leaders of the program module). I value that I-You (Buber, 1923) relationship. Note the connection to the title of the 2001 OERC Conference -- Improving Student Learning: How Do I-You Know? 12

I always look for candidates with the strongly-held values, self-knowledge and potential to learn and develop because it is easier to teach skills than values. Diana Lam (1990) then superintendent of Chelsea, Massachusetts schools wrote, "Yes, we need leaders with skills -- but skills can be learned. I do not know how to change someone's heart" (p. 1 in Sergiovanni, 1992, p.1).

|

|

|

Don Backus, elementary & secondary principal, Covey trainer and leader of the School Leadership Program. I have known Don since January, 1989. He retired in June, 2001.

|

|

These multiple roles that make up the whole of leadership constitute some of the complexities inherent in attempting to create The Knowledge Base in Educational Administration: Multiple Perspectives (Donmoyer, Imber & Scheurich, 1995). I am in agreement with James Scheurich and many of the other authors of the text that the seven categories that the University College of Educational Administration has determined to constitute the knowledge base are based on positivist thinking (p.21). In the Donmoyer et al. text (1995), Joseph Murphy refers to Jack A. Cuthbertson's (1988) historical description of the quest to describe and prescribe the work of administrators in educational settings:

After a century's pursuit of knowledge, scholars of educational administration still look to science, with its multi-faceted and changing definitions for a legitimizing cloak, facilitator of inquiry, and a tool to be used in the continuing quest for knowledge about the ends, means, and settings of a very complex social process (24) (p. 49).

The real value of this particular text is that it presents "an intellectual vaudeville" (p. 6), alternative and challenging perspectives on the arena of educational administration and what constitutes the 'knowledge'. Like Scheurich, I think there is no definitive knowledge base but that multiple perspectives are the most realistic means to capture the meanings. Donmoyer shares his experience in the field as an acting principal and finds that knowledge use in the field is characterized by serendipity (p. 94), that the "knowing what" knowledge base remains a black hole in most administrative preparation efforts and that "visceral literacy" is an essential skill (p. 87). He, too, questions the value of creating a knowledge base and after his practical experience finds himself "much more sympathetic to philosophers' talk of 'embodied knowledge'" (p. 91). Coinciding with the repeated concern in Division A sessions at AERA, 2000 and 2001 of the lack of application of academic theory in real life administrative practice, Anderson and Page (1995) support the greater recognition of practitioner research that focuses on the process of learning on the job:

Discussions should not be concerned so much with how we structure our programs or content for a knowledge base, but rather with how we choose the processes we use to engage with practitioners around the knowledge base that they already possess. Only by taking the narrativity of experience seriously can we produce dialogue and critical reflection in our programs, and model the process necessary to promote empowered practitioners and democratic institutions (p. 133).

In this same text, Shakeshaft (1995) is concerned with the androcentric nature, which she defines as "the practice of viewing the world and shaping reality through a male lens" (p. 140), of the current knowledge base in educational administration. She cites examples of distinctly different ways of perceiving administrative issues and behaviour through the eyes of women and men including supervision, sexuality and language interpretation. Her earlier research (1987) indicated that:

- Relationships with others are more central to all actions for women than they are for male administrators.

- Teaching and learning is more often the major focus for women than it is for male administrators

- Building community is more often an essential part of the women administrator's style than it is for the man (Donmoyer et al., 1995, p. 146).

In a similar vein, Bateson (1989), feels this multi-tasking, a dynamic of moving amongst the multiple intelligences, (Gardner, 1983) is a capacity which is very natural for women:

But what if we were to recognize the capacity for distraction, the divided will, as representing a higher wisdom.? Perhaps Kierkegaard was wrong when he said that 'purity is to will one thing'. Perhaps the issue is not a fixed knowledge of the good, the single focus that millenia of monotheism have made us idealize, but a kind of attention that is open, not focused on a single point. Instead of concentration on a transcendent ideal, sustained attention to diversity and interdependence may offer a different clarity of vision, one that is sensitive to ecological complexity, to the multiple rather than the singular. Perhaps we can discern in women honoring multiple commitments a new level of productivity and new possibilities of learning (p. 166).

I recognize that as I submit my original living educational theory (Whitehead, 1983, 1993, 1999) based on my understandings from the study of my practice that I will confront academics who do not value the practitioner-scholar view of educational administration, despite the fact that "Dewey's notion of educational science was one grounded in practice and the realities of schools" (Bredeson in Donmoyer et al., 1995, p. 50).

Fitting Myself Into A Leadership Model

I find as I'm writing for the purpose of integrating the work of experts in the field, that I get furious at myself (I'm not blaming anyone else). I persist in trying to fit my practical embodied knowing into their typologies. Over and over I do this and wonder at the tension that builds up every time. I am learning to take the ideas of others only in so far as they help me to reflect on my life and to resist their application as a means of explanation (as Cheryl and I did with the OCT Standards of Practice). It seems amazing that the discourse of hegemony with its impositions and controls can consistently limit my capacity to describe and explain my life. I do, however, concede that I reflect on these writings and use or discard them as they work for me. At the same time that I am complaining about the limitations of writings by academics like Fullan (1982, 1993, 1999) and Fullan and Hargreaves (1991, 1996, 1997, 1998), I must recognize my responsibility to put my own work into the public domain for public accountability as they have done.

The theory around 'transformation' works for me whether in terms of teaching and learning or in leadership (Leithwood et al., 1999) but it cannot be a model (Day, Harris, Hadfield & Tolley, 2000; Stoll & Fink, 1996). I have engaged with the ideas of the researchers but not used them in a generalized or complete way. When I think back on myself as an aspiring leader, I looked for a way to turn my sense making into a general theory or a grand narrative. I wanted to fit my experiences into the theory being offered. I asked, What is it? What is educational leadership? Gradually I found I had faith in my creativity and a confidence in my embodied knowing as part of my growth of awareness as a superintendent. I gradually recognized that for me there is no definition. Through my descriptions and explanations of my life as a leader I give meaning to my embodied knowledge on leadership. While I have read, used and integrated the traditional research, theory and writing on leadership, I have transformed that work through my own creativity so that the meanings are mine, based on my experience and research.

Writers/researchers that have influenced my thinking and doing include Peter Senge (1990, 1999), Seymour Sarason (1995), Andy Hargreaves and Michael Fullan (1991, 1996, 1997, 1998) and Gareth Morgan (1988, 1993). From Senge (1990, 1999) I used his work on "mental models, team learning and organizational learning." The concept of "mental models" was helpful in learning to challenge my own and others' assumptions and forcing myself to take a new perspective. Team and organizational learning is an essential basic for an educational system where individuals must continue to learn but the system itself must learn and grow as well.

To aid in my growing capacity to understand how systems work, the work of Gareth Morgan (1988, 1993), was very helpful in making meaning out of systems and system behaviours. Morgan (1988) used a series of metaphors to explain some of the complexity of managing complex structures in turbulent times. He talked about managerial competencies such as: "developing an appropriate corporate culture; encouraging people to learn and be creative; and striking a balance between chaos and control" (p. 69). At the time of first reading these works, I was in my first system position, Coordinator of Special Education Services for The Brant County Board of Education. His analogy of "riding the waves of change" with a list of emerging managerial competencies (1988, p. 3) seemed interesting but vague at the time. When I could combine them with my daily experiences, these images such as spider plants and termite colonies began to make sense of the system processes. In addition, at the time, 1992, I heard Gareth Morgan (1993) at a conference on planning for improvement. Shortly after that I became a school principal and that concept of "making change in your 15%." or "getting people to do a 1% improvement all over the place, [in order to] change the mindset" (p. 52) made planning with my staff more manageable.

Despite the fact that Peter Moffatt and I and other leaders in the system have been trained in Strategic Planning with its goals and objectives and strategies and action plans, we have never rigidly followed that model. Strategic plans tend to look and sound good but never really come to fruition because of lack of involvement and commitment by those implementing the plan. We have followed a vision of building 'capacity' (Stoll & Myers, 1998, p.7) so that each individual in the system would get better at planning in ways that made sense to them and to which they were committed. Annually and in three year cycles as a system we have set system areas of emphasis but each school, school community and individual must make their own commitment as to how they intend to make improvement.

I found the work of Seymour Sarason (1995) enabled me to conceptualize the power principle, the potential of inclusion of parents and community in improving schools and the barriers created by hierarchies. This connects to the arena of power relations that I have experienced with the academic world 13

and have worked to reduce in my relations with staff and my children. When I consider the concept of 'insider' research (Anderson & Herr, 1999), I reflect back on Sarason's picture of professionals as insiders and parents (and other professionals) as outsiders. I agree with Sarason (1995) when he says that when you are going to be affected, directly or indirectly, by a decision, you should stand in "some relation to the decision-making process. What prevents us from operating according to that principle is the way we define the assets and deficits of people" (p.7). I can recall early in my tenure as superintendent responsible for the implementation of the new School Councils presenting to the administrators of the former Brant County Board. In the presentation I used some of Sarason's ideas and modeled an exercise that he included in his book. I asked them to visualize a parent coming up the steps of the school and to examine how they were reacting. It is an image that I use frequently in examining my responses to people outside of the education system. When I was just learning to be a principal, Peter Moffatt said that whenever a complaint came to him he took it as an opportunity to examine how we do things and to see if there are ways to improve. I've used that many times. We have shared with principals on several occasions that the most frequent complaint we get from parents is "I wasn't listened to." Sarason (1995) reminds me to be humble: "But if we indubitably have our imperfections--and no one has ever doubted that assertion--are we not obligated to be more humble, or at least more self-critical, about the rigidity of the boundaries we erect around our profession?" (p. 26).

Moreover, this hierarchical problem exists for teachers as much as parents and "teachers are the low person on the totem pole" (Sarason, 1995, 31). This attitude also applies to students. So when I treat a principal as an equal, potentially he/she sees the teacher as an equal, so then conceivably, the teacher replicates that approach with the student and students treat each other with dignity and respect. And thus a culture can be created based on true north principles (Covey, 1992) I have seen it happen in Cheryl's classroom 14

and in Greg and Kim's schools. 15

What I have frequently articulated as an indicator of a good school is the school who sees parents and community (as well as children) as assets and resources to improve learning and I look for how many volunteers there are involved in the school. This directly connects to my standard of inquiry and reflection through non-hierarchical and democratic ways of relating and evaluation.

Even when I don't agree with a researcher/writer, I find that thinking through their work helps me to think through my own. Examining the nature of school culture and the changing systems within it (Fullan & Hargreaves, 1991; Fullan, 1993; 1999) articulated the problems and stimulated my thinking but never seemed to describe any solutions. As an example, contrary to their premise that change is a process, not an event, I think the implementation of the Conservative government's market force policies 16

has been an event. There certainly was little process. They legislated a change and the educational system has been changed. Whether this is "educational change" is a valid point. (Hargreaves et al, 2001), I am in agreement with many of Fullan & Hargreaves' (1991) "guidelines for actions" (p. 63-107) such as recognizing the power of capacity-building strategies, frameworks of accountability, collaboration, and trusting in processes as opposed to employing distant hierarchical methods of compliance. However, just writing that schools are balkanized and need to be collaborative will not change the situation (p. 52-62). In my experience, where teachers, parents and administrators identify their own issues, research their practice and find their own solutions through creative engagement, real change can take place. While I agree that action research and research-based professionalism can lead to improvement: "Teacher research, especially action research, can be a particularly effective way to link improvement and inquiry to classroom practice (Kemmis and McTaggart, 1988, Oja and Smulyan, 1989). Professional researchers don't have a monopoly on research. Teachers can do it too." (p. 71), just talking about it won't do it. That systematized knowledge (Snow, 2001) exists: it's not just teachers can; teachers are doing it. (Delong & Wideman, 1998a,b,c; Delong, 2001b; Whitehead, http:www.actionresearch.net).

Another case in point is Fullan & Hargreaves' (1991) statement that you may trust in processes (p. 74). I think that you can trust in your individual capacity to creatively engage in risk-taking that is inherent in organizational problem-solving, to learn from mistakes but it must be in each case an individual response. I can manage a situation if I feel that I am operating according to my values and true north principles (Covey, 1992) Since September, 1999, I have worked with communities to conduct school 'accommodation' studies that have frequently ended in the reorganization and closing of small, community schools. In these processes I have come to realize that it is a very individual and personal experience for each person to try to comprehend the problem, arrive at a solution and work through what is frequently a grieving process in the end. I have found no easy route or pre-planning that can short-circuit what is both a logical and emotional response to a difficult situation: a situation created by a government forcing economic rationalist policies on small, rural and vulnerable communities. It is always for me an emotionally draining process with my only satisfaction in the hope that I have tried to be sensitive to the emotions and allowed people the opportunities to vent and share their anger without taking it personally. 17

I can learn both from research that I can apply and also from research that I don't find useful. The difference between my response to Sarason and Covey and to Fullan & Hargreaves is that I feel that Sarason and Covey invite me to an "appreciative engaged response" (D'Arcy, 1999) while Fullan & Hargreaves present in a traditional, propositional and conceptual way and send a message that a theory is out there that can explain my life. I agree with Stoll and Fink (2001),

Our experience in attempting to bring about change suggests that effective leadership is a key determinant in deciding whether anything positive happens in a school or a school system (Stoll And Fink, 1988, 1989, 1994). We have arrived at a place in our thinking, however, which suggests that traditional descriptions of leadership which tend to sort leaders into categories or typologies are inappropriate for the postmodern age and the challenges it brings to educational leaders (p. 101).

I believe that I must find my meanings in the context of their use. At issue is the validity of my process of ascending from the abstract to the concrete so that my embodied knowledge is viewed as a higher form of knowledge than the traditional propositional theorizing.

The cluster of leadership works on moral leadership (Sergiovanni, 1992), servant leadership (Greenleaf, 1977) sacred dimensions of leadership (Bennis & Nanus, 1985) caring and relational leadership (Gilligan, 1982; Noddings, 1984; Bateson, 1989; Regan & Brooks, 1995) and connecting work and soul (Bolman & Deal, 2001) provided me with a feminist and spiritual/religious/moral perspective on the arena. While all of these writers have to some degree transformed my thinking, doing and theorizing, their research helped me when I have been able to integrate their meanings into my own.

Sergiovanni's work (1992) was a particular inspiration at the same time as Covey in terms of "seeing a need for an expanded theoretical and operational foundation for leadership practice" and particularly referring to this expanded foundation as the "moral dimension in leadership" (p. xiii). Much of the dominant literature during the early years of my leadership experiences (1985-1990) was focused on "management values biased toward rationality, logic, objectivity, the importance of self-interest, explicitness, individuality and detachment" (p. xiii). I was looking for inspiration from an expanded view of leadership such as Covey, Sergiovanni and Bennis & Nanus described.

The concept of servant leader is clearly described in Robert Greenleaf's (1977) work. He says: "The servant leader is servant first" It begins with the natural feeling that one wants to serve, to serve first. Then the conscious choice brings one to aspire to lead" (p. 13). While his work has a religious message, I think his influence goes beyond that. He says that caring for one another is the foundation on which good society is built. That attention to the individual and taking time to care is reinforced by Sarason (1995): "And the reason most frequently given by physicians is precisely that given by teachers: 'I have no time.' It is a reason that concedes the point that recognizing and responding appropriately to individuality is a luxury, an unassailable value or goal that existing realities cannot meet" (p.157). If goals are values (Blanchard & Bowles, 1998, p.41) and my values are my standards, despite my realities, I do not intend responding appropriately to individuality to be a luxury but a standard to which I am held accountable which the following narrative demonstrates.

|

|

|

Phillip Sallewsky, core French teacher, Masters grad and PhD student. I have known Phillip for three years.

|

|

I think that I show care through empathy, listening for the concerns of others, supporting them and spending time with them. The significance of telling the narratives struck me when one of the masters students, Phillip Sallewsky, a young man who is a very good teacher as well as a good student and who has great potential to be a school administrator, asked to talk with me privately. He talked about a situation where he was in conflict with a superintendent in another board and showed me e-mails where he had asked for a post-interview and been refused. He is a young man in a hurry and had been using an unproductive approach to problem-solving. I asked him if he still wanted a job in the other board. When he answered in the negative I asked him why he would continue the battle. He felt that he had been treated unjustly and was worried that his reputation would be damaged in discussions among superintendents. I replied that under the right to privacy legislation, his application could not be discussed without his permission. When I assured him that his reputation was intact with me, that I cared about him and that he had a bright future in our board, he seemed to relax and concluded that it would be prudent to walk away from the conflict.

I was reminded once again of the importance of spending time. His face seemed brighter and his walk lighter when he left. The conversation had the same effect on me -- I was tired and not feeling well but I felt good that he felt comfortable to share his concern, I had attended to his concern and had showed that I cared. As Cheryl affirmed, "Listening is caring. Sometimes (and I forget this) people only need to vent. They don't need you to do anything, just listen. The fact that someone cares enough to listen and, the importance they place on that person's opinion can make the listening the most important act. A reaction is not necessary many times. The difficulty is knowing which time is which" (Black, e-mail, 01/04/01).

My emphasis on building a community of interdependent learners (Covey, 1989) in my families of schools was influenced by Covey (1992), by Sergiovanni (1992), by Bennis & Nanus (1985) and by Bennis & Biederman, (1997). While none of these provided prescriptions, they stimulated my thinking on how I could use their ideas to improve the schools, to be a leader of leaders (Sergiovanni, 1992) and to serve my staff. Bennis and Nanus (1985) agreed with Mr Wildman who in 1648 thought that, "Leadership hath been broken in pieces." However, in the leaders that they studied, they saw that the sacred nature of leadership and teamwork needed to be given priority. It seems obvious but not a widely held notion that "the more people you could put to work on a problem, the more opportunities you would have to find a solution" (p.121). That approach created what they called the "collegial organization" (p. 119) which was much like what Fullan & Hargreaves (1991) described as "collaborative cultures" (p. 59) but very unlike "forced collegiality" (p. 58). Blanchard and Bowles (2001) have used the parable of the hockey team to teach that "None of us is as smart as all of us" (p.60).

In addition to Sarason (1995) and Sergiovanni (1992), this theme is reflected in the work of Gilligan (1982), Noddings (1984), Belenky et al., (1986), and Bateson (1989). My experience has been that caring is essential but insufficient in providing leadership for improving schools. For Noddings (1984), empathy "does not involve projection but reception… I do not project. I receive the other into myself, and I see and feel with the other" (p. 30). I believe that caring and empathy must be combined with critical thinking and critical judgment. And as Sergiovanni (1992) concludes, "Good leadership is a necessary but insufficient condition for successful schooling" (p. 144).

The Influence of the Feminist Literature

I have persistently resisted categorization of my work as gender research or practice. I do, however, recognize that as a woman leader, my gender is a factor in how I operate and how I prioritize people and relationships (Bateson, 1989; Gilligan, 1982; Shakeshaft, 1995). It probably seems obvious to anyone who looks at the group of superintendents below to see that I am the only woman on the Brant and Grand Erie teams, with the exception of the Transition Team (1998) which included two women for a few months. People like Cheryl Black, Maria Birkett and Marion Kline tell me that I am a role model as a female leader. I resist the gender bias because as a postmodernist I resist categorization. I don't want anyone to view my leadership as restricted by my gender but rather enhanced by it. I have worked hard be a good leader not solely a female leader and many men that I work with value relationships to the same degree that I do.

|

|

|

Executive Council Members, Brant and Grand Erie from 1994-2001:Colin Armstrong, Bill Leeson *, Gerry Kuckyt, Jim Grant*, Peter Moffatt, Ken Bell*, Jackie Delong, Dan Dunnigan, Wayne Thomas*. * - retired

|

|

I have come to appreciate the work of Gilligan (1986), Noddings (1984), Bateson, Belenky et al. (1986) and Regan and Brooks (1995). While I do not want to spend my time on the bifurcation caused by 'either-or' approaches to understanding myself and the world or by suggesting that the female way is better than the male way, I found myself nodding in agreement with many of the stories of the women in Women's Ways of Knowing (Belenky, et al., 1986). My growing confidence and capacity in becoming a leader has come about from listening to, valuing and integrating the voices of others as well as respecting my inner voice. I often speak of my connected way of doing things, of being able to see the relationships and connections amongst the various aspects of my personal life and complexity of roles in my job. "Connected knowing involves feeling, because it is rooted in relationship; but it also involves thought" (p.121). I could identify with "Women don't just learn in classrooms; they learn in relationships, by juggling life demands, by dealing with crises in families and communities" (p. xi). The authors describe five epistemological perspectives from which women know and view the world: silence, received knowledge, subjective knowledge, procedural knowledge and constructed knowledge (p. 15). In my life I can see all of these ways of knowing and although not in any linear sequence, the trajectory of my development toward "constructed knowing" has become sharper in the years of my research on my practice. They describe "constructed knowing" as "learning to use the self as an instrument of understanding to arrive at passionate knowing" (Belenky, et al., 1986, p. 141).

When I first entered into leadership roles I followed a very male pattern of leadership where objectivity, logic and facts-based internal analysis were valued. "Prior to the 1980's, women had to demonstrate to male superiors their ability to make tough decisions and be more efficient than male counterparts" (Stoll & Fink, 2001). In fact there were few female role models to emulate or talk to, which Regan & Brooks (1995) say is common in the studies they have conducted. I reluctantly refused to listen to my intuition and my experience which was considered soft data. In the past ten years through Howard Gardner's (1983) work on multiple intelligences and Coleman's (1997) and Stein and Book's (2000) work on emotional intelligence, listening to gut feelings and hunches and inner voices has become more valued. Belenky et al. (1986) say: "This interior voice has become, for us, the hallmark of women's emergent sense of self and sense of agency and control" (p. 68).

However, one of the real dangers here lies in any continuation of the dichotomy caused by thinking that one way of knowing and being is superior to another:

Reliance on authority for a single view of the truth is clearly maladaptive for meeting the requirements of a complex, rapidly changing pluralistic, egalitarian society and for meeting the requirements of educational institutions, which prepare students for such a world (Belenky et al., 1986, p. 43).

I agree as well with Bateson (1989) that we need to recognize "the dangers of devotion to the superiority of any group, gender, race, religion, or nation, or even to the truths of any era. The real challenge comes from the realization of multiple alternatives and the invention of new models" (p. 62).

It was a seminal event in my life when I recognized that the difference between the way my thinking and learning worked and Peter Moffatt's. I can't put a specific time on it but I do remember a conversation in his office early in my tenure as superintendent. I think we were discussing our profiles on the Myers-Briggs Inventory, a scale that measured our leadership styles. I remember saying to him that what was preventing me from being as effective as I might on Executive Council was that everyone was an introvert except me; I am an extrovert. I meant that all of the others processed information internally and individually and I processed information through thinking out loud and in dialogue. The others would come to the meetings with fully analyzed, fully completed reports and expect my support without any discussion. At first I associated that characteristic solely with my being extroverted but as I read Belenky et al. (1986), Tannen (1990) and Gilligan (1982) I began to see that it is also associated with my gender. Not only is the talk part of my learning, it is also part of my need for intimacy and relationship. Belenky (1986) makes a distinction between real talk and "didactic talk in which the speaker's intention is to hold forth rather than to share ideas"(p. 144). What constructivists call "real talk", Jurgen Habermas (1982), called a kind of ideal speech situation: "Speech that simultaneously taps and touches our inner and outer worlds within a community of others with whom we share deeply felt, largely inarticulate, but daily renewed inter-subjective reality (p. 620 in Belenky, 1986, p. 146). By my articulating my dialogic learning style, Peter has become more responsive to my needs.

Gilligan's (1982) work is significant to me in terms of understanding the emphasis I place on relationships with people. I wouldn't say that the relationship is of sole importance but it is essential to me to give meaning and purpose to my life and work. Because I find it extremely hard to work with someone who is very negative or totally pragmatic, I gravitate to people who have a passion for life and a will and commitment to make things better. When I combine care for the other and responsibility to improve things I find real satisfaction in an endeavour. Gilligan traced the development of a morality which combined care and responsibility which she saw as dominated by women as opposed to a morality of rights more commonly practised by men (pp. 160, 163-164).

But approached from different perspectives, this dilemma generates the recognition of opposite truths. These different perspectives are reflected in two different moral idealogies, since separation is justified by an ethic of rights while attachment is supported by an ethic of care (p. 164).

She says that women perceive and construe social reality differently from men and that these differences center around experiences of attachment and separation (p. 171) She goes on to say that there is a need for research on adult development that delineates "in women's own terms" the experience of adult life.

...The concept of identity expands to include the experience of interconnection. The moral domain is similarly enlarged by the inclusion of responsibility and care in relationships. And the underlying Greek ideal of knowledge as correspondence between mind and form to the Biblical conception of knowing as a process of human relationship (p. 173).

In the development of my career, I see myself reflected in Gilligan's (1982) thoughts on mid-life development (p. 171). As my children matured, I grew more independent and focused more on career achievement at a time when most men had reached their goals. Question-posing which Gilligan (1982) says is at the heart of the responsibility orientation is fundamental to my connections with people. The questioning is part of a moral imperative to improve the educational system for the teachers and children in it.

One of the strategies I have used frequently to develop my skills of listening in "conversing in the connected mode" (Belenky, 1986, p. 114) is a combination of forbearance, patience and "intentional passivity" (VonWright, pp131-32 in Belenky, p. 117). According to Noddings (1984):

I let the object act upon me, seize me, direct my fleeting thoughts "My decision to do this is mine, it requires an effort in preparation, but it also requires a letting go of my attempts to control. This sort of passivity ... is not mindless, vegetablelike passivity. It is a controlled state that abstains from controlling the situation (p. 165).

An example of that attention to the other, of empathetic listening (Covey, 1989), of a deliberate willing passivity can be seen in my role in the Secondary Teachers Action Research (STAR) meeting of May 8, 2000. This network was started by Dave Abbey and continues to be supported by him and Lynn Abbey. I remember asking him if he wanted me to attend the first meeting of the group and he said he thought it would go better without my presence because of my position. That was very astute of him and I respected his honesty. I was, however, invited to the May, 2000 meeting and was very conscious of being in the background. That capacity has come about as a result of a concern expressed in my evaluation done by the principals and vice-principal in the PJ family of schools in June of 1995, of my increased awareness of the power of my position and of my improvement in the interim. 18

"Patience," says the writer Simone de Beauvoir (1976), "is one of those 'feminine' qualities which have their origin in our oppressions but should be preserved after our liberation" (Belenky, 1986, p. 153).

The imagery of living life as improvisation resonates with me. Mary Catherine Bateson's book, Composing a Life (1989) connected with Richard Winter's (1998) definition of action research as improvisatory self-realization (p.371). Bateson (1989) starts the book with, "This is a study of five artists engaged in that act of creation that engages us all--the composition of our lives. Each of us has worked by improvisation, discovering the shape of our creation along the way, rather than pursuing a vision already defined" (p. 1). What I particularly liked about this book was that it was a collaborative effort of the five women involved and although the dominant voice is that of Bateson, she talks about her wish to give equal value to all their voices and about her struggle to accomplish that intention. That intention reflects back on the collaborative work of Cheryl Black and I. 19

There are many books studying women's lives (Belenky et al, 1986; Dadds, 1995; Marshall, 1995; Regan & Brooks, 1995) but few like my own that is my own study of my life. I found the stories in Composing A Life (Bateson, 1989) reflected my own life with "their pathways into zigzags or, at best, spirals" (p. 233). One of the attributes that has increased my capacity to be flexible, resilient and to deal with ambiguity is just the sorts of experiences that I share with the women in the book. I think I have lived as if "composing a life involves an openness to possibilities and the capacity to put them together in a way that is structurally sound" (p. 63). In my work I ask as Bateson did, "But what if we were to recognize the capacity for distraction, the divided will, as representing a higher wisdom?" (p. 166). And "Instead of concentration on a transcendent ideal, sustained attention to diversity and interdependence may offer a different clarity of vision, one that is sensitive to ecological complexity, to the multiple rather than the singular" (p. 166). Like Bateson and her friends, "[I] work too hard, burning too many candles, driven by a sense of how much needs to be done"(p. 237).

In Out of Women's Experience: Creating Relational Leadership, (1995), Regan & Brooks base their view of relational leadership on a way of re-framing a patriarchal society which they view as a "broken pyramid" (McIntoch, 1983 in Regan & Brooks, 1995, p.13), through "relational knowing" (Hollingsworth , 1992a in Regan & Brooks, 1995, p.79-80) to form a metaphor of a double helix to symbolize the concept of relational administering (p.19-22). "Hollingsworth (1992a) located relational knowing at the intersection of three bodies of knowledge: theories of social construction of knowledge, theories of feminist epistemologies, and theories of self/other relationships" (p. 79). In their conclusion, Regan & Brooks (1995) say:

Although we know that relational leaders exist (we think of ourselves as such), to our knowledge, no one, including ourselves, has examined leadership through this lens. That is a project for the future, which will require the efforts of scholars familiar with the classical and emerging literature on leadership, as well as reflective practitioners of both genders who have consciously integrated masculinist and feminist attributes of leadership in practice (p. 93).

My study contributes to an increased understanding of a relational way of leading. To effect improvement and change, I find that caring and empathy needs to be combined with critical and creative thinking and critical judgment.

Working to Reduce Hierarchies

My need to reduce hierarchies may bear some relationship to the high regard I have for the work of educators and what Martin Buber (1947) says about humility and the values contained in the glance:

If this educator should ever believe that for the sake of education he has to practise selection and arrangement, then he will be guided by another criterion than that of inclination, however legitimate this may be in its own sphere; he will be guided by the recognition of values which is in his glance as an educator. But even then his selection remains suspended, under constant correction by the special humility of the educator for whom the life and particular being of all his pupils is the decisive factor to which his "hierarchical" recognition is subordinated. For in the manifold variety of the children the variety of creation is placed before him (p. 122).

I think I can provide some evidence of this value in my relationships from an observation of Fran Squire, Project Manager at the Ontario College of Teachers:

What is remarkable about you as a superintendent is the non-hierarchical nature of your relationships with your staff and your commitment to relationships. This is evidenced in the time you commit. Other superintendents 'drop in' to sessions like this while you stay and participate. When I asked her if she felt any tension or reluctance in the focus group because I was there, she said she saw none and in fact felt the very opposite in that they felt comfortable to articulate their beliefs and reservations. For example Pat the kindergarten teacher talked about her unease in the first session which was caused by her concern about how the standards of practice would be applied (transcript of OCT standards workshop, 1999).

After the focus group, Janet Rubas, program consultant, commented about how good it felt to hear a superintendent in her board articulate a philosophy of moral leadership, a philosophy focused on caring and respect for people, both children and adults.

Living Life As Job Training

I was interested to listen to the work of Irene Karpiak (2002) on autobiography and adult learning at AERA 2002 in New Orleans. She talked about adult learning as being transformative in that:

It is learning that permits a more inclusive, differentiated, and integrated view of themselves and the world (Mezirow, 1991; Tennant & Pogson, 1995). Central to transformative learning is critical self-reflection, whereby adults engage in a process of examining the cultural and personal assumptions and meanings that underlie and shape their view of life (Mezirow, 1991; Brookfield, 1987). Whereas critical reflection calls largely upon the learner's rational processes (Mezirow, 1991), it also includes intuitive and emotional dimensions.

Here is a story that I think reflects rational and emotional processes of reflection and learning. During 1998-2001, I was responsible for the organization and process of holding public meetings studying possible school closures and reorganization in my family of schools. On November 24, 1998, I stood in front of the group of three hundred angry community members in the Valley Heights Secondary School auditorium prepared with my slide show full of data covering the facts and graphs of the situation. 20

I was feeling the animosity in the room and knowing, as much as anyone can fully know, that this would not be a pleasant evening. The committee members sat at the front in a row looking uncomfortable as well. When the chairman, a trustee from the area, explained the process and asked me to review the current situation, people in the audience were speaking out and each time that I attempted to go through the slides projected from the computer, they would interrupt with questions and comments. I attempted to continue but on several occasions I deferred to the chairman for direction. With quiet determination and a slow and steady delivery, I reviewed the slides. Later, in the same professional and calm manner, I attempted to answer the questions directed to me.

I felt attacked but worked very hard not to show my anger or discomfort. When I was asked how I maintained the professional calm demeanour, I answered that I just kept a tape running in my head that said:

- This is not a personal attack

- There is no reason that they should be happy about this

- Your parents taught you to treat everyone with respect.

Where did this capacity come from? It comes from growing up in a family where values of respect and dignity of the other were lived. It seems to me that it may be partly at least from twenty-three years of living with and dealing with aggression. Over that time (1970-1992) I learned coping mechanisms to deal with aggression from my husband: pacify, circumvent, avoid and ignore. With a vision of my children's safety and wellbeing in mind, I steeled myself to the aggression and visualized where it might come out.

With the Valley Heights Accommodation and Consolidation Study, I looked to solving the financial problems and the program needs as the long-term vision recognizing that the study process would not win any friends. I had a sense of not locking into the anger, of being the consummate professional and of rising above the fray and protecting the values that I stood for. Maybe I have my ex-husband to thank for my capacity to withstand the barrage of aggressive behaviour. I wonder if I had had only pleasant experiences if I would have this capacity. In any case, life experiences better equipped me to deal with the aggression of these public meetings. Carol Gilligan (1982) describes this as the maturity of experience. This may be part of my preparation for leadership but I don't recommend the means!

Combining the Personal and the Professional

I was cautioned at one of the Validation Group Meetings (2000) by one of the members about including my personal and family life. This opinion was not held by the entire group and is not held by Michael Erben (1998):

Biographical investigation must involve the continual examination of the interplay of family, primary group, community and socio-economic forces. To explore one without the others is to impoverish interpretation.

As such, while the researcher must contextualize lives within economic conditions, they must also seek to comprehend their specificity (p. 9).

I have shared my relationship with friends, Diane Morgan, Cheryl Black and Peter Moffatt. I think it is also necessary to understand the context of the narrative of the professional educator where I am living that divided will and multiple commitments (Bateson, 1990, p166) fulfilling multi-roles, one of which is mother.

Stephen Covey (1992) says that there are four human needs: to live, to love, to learn, to leave a legacy. I think the most significant legacy that I leave is my children. I make no claims about being the perfect mother but I do feel pride in the strong young people that they are and I feel I can take some credit. Children learn more from who you are and what you do than from what you say. They have seen a committed, hard-working person who cares for them and others and who gives them unconditional love. I taught secondary school students for six and a half years before they were born. As a stay-at--home Mom with pre-schoolers, I centred my life around them and worked at being a homemaker with the same intensity and commitment that I give to all that I do. Shannon wrote,

My earliest memories are of my mom staying home with me and my older brother Dean. To sum them up, she could have given Martha Stewart a run for her money in everything from homemade strawberry-rhubarb jam (grown in the backyard) to the little dresses that she sewed to put clothing on my back...

So, even when she wasn't "working", she was. She wasn't a "teacher" but she was a "mother" and to her, that meant doing her best at the job at hand, especially when it came to her children. And anyone who has worked with my mother knows that her best is nothing short of perfection.

Perhaps that is why I had difficulty when my mother went back to work, first only part-time, then full time when my brother and I were in school. It's hard to admit now how I resented it. I'd had too much of a good thing and I put up a fight to keep it. But it wasn't many years before I saw, what took me longer to fully understand, was that working is important to my mom. And more than that, that what she does doesn't just matter to her, but is a big part of who she is and how she defines herself (Foerter, August, 1999).

As I entered back into the workforce, Dean was going to school full time and I started back half-time as Shannon was in half-day kindergarten. I struggled for two years to get back to a teaching position with a permanent contract and some tenure. Juggling husband, children and a job was demanding but I was happy to be back at work. As they grew older I started doing volunteer work for the teacher union and later was elected to a salaried position (District President). I moved into increasingly responsible positions with the board from Department Head to Coordinator of Special Education Services to Principal.

Shortly after my appointment to my second principalship, my marriage fell apart. Both of the children went through a difficult time when my marriage dissolved, a marriage that I was trying to hold together for them. You do what you think is best at the time and afterthought is always right.

My parents separated when I was sixteen. While it wasn't a surprise, and we could all see that it was for the best, it was tough. They had put a lot of years into the marriage thinking that stability meant two parents in the same house when their kids thought they should find some way to be happy apart. While this is one difficult issue we had, at least by sticking to their decision, my brother and I were both old enough to understand what was happening and to be an active part in that. I think waiting helped us see that is was the right course of action and that blame is irrelevant. But watching my mom struggle through gracefully taught me a lot (Foerter, August, 1999).

Dean was at University and Shannon was home with me. I don't know who had the harder time. Shannon lived in the middle of it and Dean heard about it second hand. Shannon and I grew very close over the adjustment years of 1993-1995. I was trying to move on to a new cycle of my life. It came in the form of a new job-a superintendency for the Brant County Board of Education. Shannon started University and I poured myself into the new role.

Now they are both graduates. Dean is married and working as an account supervisor in a Canadian advertising company in Toronto; Shannon is a staffing consultant in a career placement firm in Mississauga. They are intelligent, hard-working and caring individuals and when I look at their wedding and graduation photos, I feel proud of my legacy (Covey, 1992).

Sending That Message of Faith In the Other

A recurring theme in my relationships with people is my capacity to see their potential and to relay it to them where they had not seen it before. There is evidence in my daughter, Shannon, who was explaining to her new boss where her confidence came from, "Mom always sent us (Dean and Shannon) the message that there was nothing that we couldn't do" (conversation, July 29, 2001). This theme runs through the stories of Kim Cottingham 21

, Cheryl Black 22

and Marion Kline (see below), keeping in mind that

Between interpretations of a stimulus and response, individuals have a conscious choice of how to behave, based on their knowledge and perceptions. To say, therefore, that one person can motivate another is to deny free will. A leader can create a context in which a person is inclined to act in preferred ways, but -- from the perceptual point of view -- cannot motivate someone, any more than on can oblige love or any other human emotion (Stoll & Fink, 2001, p. 108).

I know that the following is a very long e-mail but I feel that it captures my valuing the other standard of practice and judgment which is revealed in dialogical and dialectical ways. Here are Marion Kline's (e-mail May 29, 2001) views on my way of being a superintendent who values her:

|

|

|

Marion Kline, classroom teacher, now teacher consultant, one of the masters grads. I have known Marion for three years.

|

|

Dear Jackie.

I had my interview for the teacher consultant position. I arrived about a half an hour early and had on the new suit I had bought for the interview. I felt good about how I looked because I wanted to give a first impression of being very professional. I had practiced quite a bit for the interview in front of my bedroom mirror and made a mental chart in my mind of the areas that I suspected they would ask about. However, a funny thing or maybe a twist of fate happened when I arrived. It seems that the interview team was running slightly behind and so Greg Anderson came out and introduced himself and then took me to the staff room to wait so that I could be more comfortable during the wait. I helped myself to half a cup of coffee and read a little of the newspaper. I think that instead of being nervous during that time, it worked in just the reverse way. When they came to get me I felt relaxed and confident. A year and a half ago I entered this Master of Education program as a person with low self esteem and low self-confidence. When I complete this program one of the most important things that I have gained is the confidence to believe in myself.

During the first course I rarely spoke and was greatly impressed by the knowledge and confidence of some of the others. As I began to research my question, video tape myself and read I began to understand the value of my lived experiences in the classroom. At times waves of self-doubt would come back to me as voices of my past impressed on me my imperfections and inadequacies. There were times when I picked up the phone and called you.

You always had time for me. We talked on the phone so comfortably and openly that I believe those conversations kept me in this program. Everyone should have a someone to talk to like you. You are such a good listener and sincerely cared about me. You gave me advice with dignity. If we were really talking right now you would say, Marion how do you know? What did I do that made you feel that way? I know you sincerely cared because of many little things you did. During one phone call you immediately said, "When can we meet?" The reaction was so genuine and you so honestly wanted to help me that I will never ever forget the tone of your voice and the speed of your reply.

The another time that I recall right now was when I told Cheryl that I had called you and had such a great conversation with you. I was telling Cheryl how much I feel inspired and ready to write after talking to you. Cheryl told me that you valued our conversations as well. That really made me feel good. You are a little like a lighthouse for me. You keep me focused on where I am going. You have always supported me but at the same time let me find my direction on my own.

So back to the interview. When I went in I had conversation with the interview team. My answers conveyed the person I am, who really, really believes that I can improve student learning by supporting other teachers with dignity the way you have supported me. My rehearsed answers did not come out as stiff or prepared but blended into natural confident and articulate statements about my beliefs and abilities.

One experience that significantly changed me was the conference we went to in December at OISE. Sitting on the panel and articulating my research question to others was a huge leap. The reaction of those in attendance was very significant. That experience really validated my belief in me. One participant at the conference came up to me and asked if I was doing a workshop because she liked what I had to say and wanted to find out more. I also was approached in the elevator by another participant who appreciated and valued what I had said.

When the interview came to an end Greg Anderson ask me if there was anything I wanted to share that I felt had not come out in the interview. I smiled and said " You may not know this yet, but I am the right person for this job. I can support teachers with dignity to improve student learning in Grand Erie." When I finished Greg Anderson commented something about me having made quite an impression and created a feeling within the room. When I left I felt really good. I had done the best job that I could do. I had no regrets. The genuine Marion had shone through. I was so proud of myself. Marion.

I think my way of sending that message of faith in the other and valuing the other shows some connections to what Stoll and Fink (2001) call invitational leadership:

Leadership is about communicating invitational messages to individuals and groups with whom leaders interact in order to build and act on a shared and evolving vision of enhanced educational experiences for pupils. Invitational leadership is based on four premises: optimism, respect, trust and a purposefully invitational stance. Their actions are intentionally supportive, caring and encouraging (p. 109).

Once again I think that I-You relationship is involved here as "he will be guided by the recognition of values which is in his glance as an educator" (Buber, 1947, p. 122). The success of the people that I coach and mentor is also my legacy (Covey, 1992).

Why is There No Simple (or Even Complex) Answer to the Question 'What is Educational Leadership?'

On March 14, 2001, I attended a lecture arranged by Louise Stoll at the University of Bath by Dr. Alma Harris, one of the authors of Leading Schools in Times of Change (Day, Harris, Hadfield, & Tolley, 2000). The lecture was interesting and informative in terms of recent research. Using twelve case study schools the authors researched the fit between theoretical models, transactional, transformational, pedagogic/instructional, moral and emotional, and current practice. Alma's conclusion was that there is no single model for leadership and that it is a very values driven and emotive experience. Having said that there was no single theory that could explain leadership and recognizing the irony in it, she then went on to describe her theory as a result of the research: Post-Transformational Theory! She outlined the characteristics of effective leaders:

- High expectations of self and others

- Tangible, communicated sense of professionalism

- Central focus on care and achievement of pupils

- Ability to create and maintain learning culture for staff and students

- Toughness of vision, clarity of values

- Created, maintained and monitored relationships

- Entrepreneurial, risk takers, net workers

- Made tough decisions

- Acknowledged failure but learned from it

- Possessed Leadership repertoire

- Recognized and managed ongoing tensions and dilemmas in a principled way

She also articulated the tensions they face such as "Leadership versus Management" and "Personal Values versus Institutional Imperative" but made no connection between the two. She recognized in the discussion that there was nothing in the characteristics that dealt with coping with the tensions and moving forward, no connections between values, the process of connecting with your values and living those values even though it was all about living those values. Sounds like the dilemma of defining leadership!

Stoll & Fink (2001) support this transformational leadership model with reservations:

While these conceptions of leadership are the subjects of research and journal articles, reality in schools is significantly different. Southworth (1994), observing leadership in British primary schools, concluded: 'While these categories help us to classify heads as transactional or transformational, they do not capture the character and nature of leadership in action. They are too abstract and omit the vigorous quality of headteachers at work' (p. 18) (p. 106).

It would appear that no single leadership model adequately describes the expectations and reality for contemporary educational leaders (p. 107).

With regard to the order of things, I am beginning to recognize as a pattern in my research and thinking the congruency in my epistemology, my ontology and my methodology. I recognize it as a pattern in my work that is different from others. I start with describing and explaining my experience in my writing and thinking and then move to the theorizing about it. I believe that this is what is different about the epistemology of practitioner scholars and the way in which Donald Schön (1995) felt that Boyer's (1990) new forms of scholarship would challenge epistemological, institutional and political issues in the university (p. 27). Traditional academics start with theory and then apply it to their own or someone else's practice. Another's thoughts and theory cannot explain my life. And I have found myself attempting to do just that.

In practice I find that I begin my thinking and writing with a narrative of real, lived, insider experiences, events in my practice. That narrative is not simply a list of a sequence of events. It also incorporates my reflective thinking on the experience, in and on the writing of the narrative, during and after the conversations that I have had at all of these stages in the refinement of the understanding of the learning and improvement. And they are different reflections out of which arise new learnings. What is problematic is that closure is elusive. Learning to improve oneself is very messy, is never concluded and refuses to be tied neatly in a bundle for final offering. That is not to say that the product, even if not perfect, is not important. I do not want to find myself in the sorry predicament of the editors, Grant and Graue (1999), of the Review of Educational Research when they realized that they had failed to attain their purposes as editors. Nor do I wish to end my career with the palpable sadness and regret of David Clark (1997).

And now for my answer to the meaning of educational leadership. I feel that I am showing how I hold together those tensions and contribute to moving the system ahead over time. My theory is that in order to be an effective leader, I need to research my practice to form my own living theory of education (Whitehead, 2000). The only 'model' that I know that works is to recommend that each person develop his/her own living educational theory to discover the values that are their standards by which to live and be accountable. I am 'modelling' this approach to leadership in my system. Two of the masters graduates have followed this path and are continuing the process of refinement of those living standards as am I. (Black, 2001; Knill-Griesser, 2001). I know that having researched my practice I am more able to articulate my values as the standards of practice and judgment for which I wish to be held accountable and that I know my school system in a depth that I didn't before the research. I hope that I am "learning to use the self as an instrument of understanding to arrive at passionate knowing" (Belenkey et al, 1986, p. 141). I know that it is a great time to be a leader and I am excited about the challenge.

I conclude this chapter on leadership with George Bataille's (1962) words:

It is not necessary to answer the riddle of existence; it is not even necessary to ask it.

But the fact that a man [woman] may possibly neither answer it nor even ask it does not eliminate that riddle.