|

|

|

'How can I improve my practice as a superintendent of schools and create my own living educational theory?': Jackie Delong

|

Chapter Five: The Methodology of Meaning making

In this chapter on my methodology of meaning making, I share the way in which I have made meaning out of the data archive that I have collected, analyzed and validated over six years as a superintendent. In my dialectical and dialogical way, I ask and answer the questions: Why did I choose the action research process? What approaches did I use to conduct my research? and How have I validated my claims to know? I explain how my mode of inquiry has been influenced by a living educational theory approach to action research (Whitehead, 1989, 1993, 1999). By this I mean that the story of my research is a first person inquiry into my own learning and knowledge-creation between 1996-2002 in a Ph.D. program as I ask, research and answer the question, "How can I improve my practice?"

My theorizing emerges naturally from the narratives of my life as a superintendent in a self-critical process of judging my work in terms of its coherence within my values as standards of practice and judgment and from public accountability by sharing my stories. The assessments and evaluations of friends and family, professional colleagues and practitioner and academic researchers have informed my practice and theory.

Why Did I Choose This Action Research Process?

Choosing action research as my process of choice, according to Kushner (2000), may stem from my values, my socialization, my problem, my experience or as Stake (1995) says, a search 'for understanding the complex interrelationships among all that exists.'

A distinction between what knowledge to shoot for fundamentally separates quantitative and qualitative enquiry. Perhaps surprisingly, the distinction is not directly related to the difference between quantitative and qualitative data, but a difference in searching for causes versus searching for happenings. Quantitative researchers have pressed for explanation and control; qualitative researchers have pressed for understanding the complex interrelationships among all that exists (Stake, 1995:37 in Kushner, 2000).

The action research process with 'I' at the centre answering questions of the kind "How do I improve my practice?" resonated with me because of the nature of the question that the living theory approach addresses. I had been looking for ten years, subsequent to the completion of my masters degree, for a research process that was qualitative, rigorous, and practical in the sense of helping me to improve my work in helping teachers and school administrators to improve the learning of students. In my masters program I had studied research methods which were mostly quantitative, objective and grounded in social science and knew that that was not a route I wanted to follow. I was concerned with the inability of propositional forms to explain my life because they appear to deny the experiential meanings in my practice. I wanted a method that allowed for my creativity to ask my own questions and integrate my own insights.

The reading I had done on leadership was mostly theoretical and 'about' leadership. It was during the first year of the action research project with the Group of Seven 1

that I heard Jack Whitehead speak at the first Act Reflect Revise Forum in Toronto, and with his help put the pieces together that I might conduct the kind of research that I was supporting the teachers to do.

I knew intuitively that I was not looking to follow a pre-defined method that would confine my creativity. Other graduate students I knew talked of finding a model or framework for their research. I felt that this living educational theory of action research would allow me the "methodological inventiveness" (Dadds & Hart, 2001, p. 166) that I would need to theorize about my life and work. I knew that I could not simply choose a method but that as I conducted the research I would continue to question the appropriateness of the approach in a methodology that fit my purposes. I think you will find that my process of research has been emergent. It has supported the development of my epistemology and is inherent in my ontology, particularly in my postmodern resistance to rules and structure.

We have understood for years that substantive choice was fundamental to the motivation and effectiveness of practitioner research (Dadds, 1995); that what practitioners chose to research was important to their sense of engagement and purpose. But we had understood far less well how practitioners chose to research, and their sense of control over this, could be equally important to their motivation, their sense of identity within the research and their research outcomes.

We now realise that, for some practitioners, methodological choice could be a fundamentally important aspect of the quality of their research and, by implication, the quality of the outcomes. Without the freedom to innovate beyond the range of models provided by traditional social science research or action research, the practitioners in our group may have been less effective than they ultimately were in serving the growth of professional thought, subsequent professional actions or the resolution of professional conflicts through their research. In this, we find ourselves sympathetic to Elliott's claim (1990:5) that 'One of the biggest constraints on one's development as a researcher, is the presumption that there is a right method or set of techniques for doing educational research' (Dadds & Hart, 2001, p. 166).

Action research has the potential of creating important new knowledge about teaching and learning. I like Michael Bassey's (1995) book, Creating Education through Research and what he says about research contributing to public knowledge:

In research in educational settings a claim to knowledge is likely to be about some theoretical aspect of teaching and learning, or about educational policy, or about teaching or managerial practice. It may, for example:

- contribute incrementally to the accumulated knowledge of the topic under study;

- challenge existing theoretical ideas;

- offer significant improvements to existing practice;

- give new insights into policy;

- introduce a new methodology of potential power;

- provide a 'significant piece in a jigsaw of understanding'; or

- bring together disparate findings and integrate them into a new theoretical structure (p.71).

The action research process with "I" at the center developing one's own living educational theory (Whitehead, 1989; McNiff, 1992; McNiff, Lomax & Whitehead, 1996) fulfills all of Michael Bassey's criteria for contributing to public knowledge.

I see the creation and testing of educational theory as a fundamental purpose of educational research. The BERA booklet on Good Practice in Educational Research Writing (2000), incorporated the development of educational theory in its two main thrusts:

There are two main thrusts to educational research, viz.:

(a) to inform understandings of educational issues, drawing on and developing educational theory, and in some cases theory from related disciplines (e.g. sociology, psychology, philosophy, economics, history, etc);

and

(b) to improve educational policy and practice, by informing pedagogic curricular and other educational judgements and decisions. Much research includes both of these purposes, some contributes mainly to one (p. 85). 2

I recognize that my understanding of educational theory does differ from many educational theorists. The difference is focused on what counts as a demonstration of originality of mind and critical judgement in a substantial contribution to knowledge. It is focused on the nature of the standards of practice and judgment which can be used to test the validity of a claim to educational knowledge. In response to "tradition-constituted and tradition-constitutive enquiry", MacIntyre (1990) says,

The rival claims to truth of contending traditions of enquiry depend for their vindication upon the adequacy and the explanatory power of the histories which the resources of each of those traditions in conflict enable their adherents to write (p. 403).

I identify with Phillip Sallewsky (2000) 3

, a Brock University-GEDSB Masters student taught by both Jack Whitehead and myself, when he articulates very clearly his reasons for choosing action research:

My reasons for the choice of this approach is that it is the only methodology which embraces the inclusion of the 'I' of the practitioner-researcher as a legitimate focus for research. Action research accepts the notion that the researcher does not need to be external to the study in order for the information and results found to be valid. This is a major shift in thinking and presents a unique opportunity for the researcher since the motivation for researching comes from within, i.e. the researcher's desire to improve his/her practice (Whitehead, 1989). This approach also represents the sequence that I know I work at to improve my practice. Firstly, I analyze my practice and find an area that needs improvement. Secondly, I try to imagine ways and set up a plan in which to bring about this improvement. Thirdly, I act on this plan and collect data on the effectiveness of my plan in terms of my practice and lastly, modify my plan with regard to my goals and the data previously collected.

While my plan is progressing I consult with peers from my Master's course, my professional context and my life and present findings and results for critical discussion. They in turn are asked to judge my work constructively and offer suggestions as to how I can improve and/or change my inquiry (p. 81).

I have two primary purposes in writing this thesis. One of my purposes is to describe and explain my living educational theory (Whitehead, 1989, 1993, 1999) by telling the story of my life as a woman manager in an educational administrator position and to offer it as personal practical knowledge (Connelly & Clandinin, 1999). I am contributing to that new scholarship of enquiry (Schön, 1995; Whitehead, 1999) as I work to improve my practice and create new knowledge to add to the academic knowledge base of the superintendent. The other purpose is to demonstrate and explain the impact on improving learning and teaching when teachers and administrators in my district conduct action research, researching questions of the kind, 'How do I improve my practice?' (Whitehead, 1989, 1993, 1999). I believe this purpose extends as well to improving schools as described by Colin Smith (2001) in "School Learning and Teaching Policies as Shared Living Theories: An Example." and to influencing social formations (Bourdieu, 1990).

To accomplish my purposes, I use a number of genres within the action research process including narrative, auto/biography and self-study. Zoe Parker (1998) captures the dilemma of definition in this kind of inquiry:

Within the qualitative approach to enquiry, narrative enquiry is a significant strand. Within narrative enquiry, auto/biography is a further strand. This simple taxonomy allows one to situate auto/biography as a genre of enquiry. This carries with it advantages of clarity and difficulties of over-simplification. These are parallel to those one encounters when attempting to define literary genres and place individual works within specific genres. As soon as one defines a text within a box or boundary, the test defies its placement there. It reveals complexities which question its unproblematic situatedness within the genre: one where it has been trapped (p. 116).

I concur with Parker's (1998) analysis of the challenge of research in education and especially propositional arguments in the postmodern era and yet you will find evidence of traditional arguments in my thesis:

The problematics of postmodernism force one to recognize that any proposition is questionable. Postmodernism critiques research in education as powerfully located in a modern, progress oriented, and humanistic enterprise. Education has been and remains a project which is concerned with the development of each individual's potential (as discussed by Usher and Edwards, 1994, pp. 24-32, for example) (p.116).

In this action inquiry I explore the nature of my educative influence as a superintendent. Through the writing and analysis of narratives, I express, define and communicate my valuing of the other in the midst of hierarchical and power relations as a living standard of practice and judgement for testing the validity of claims to educational knowledge and theory. My "landscape is personal, contextual, subjective, temporal, historical, and relational among people" (Clandinin & Connelly, 1998). Through the description and explanation of my life, through the creation of a professional identity (Clandinin & Connelly, 1999) by storying (Carter, 1993) and re-storying my life and through insider (Anderson & Herr, 1999) practitioner research, a knowledge base of what it means to be a senior educational administrator emerges.

As well I found the work of Judi Marshall (1999) on living life as inquiry resonated with me:

By living life as inquiry I mean a range of beliefs, strategies and ways of behaving which encourage me to treat little as fixed, finished, clear-cut. Rather I have an image of living continually in process, adjusting, seeing what emerges, bringing things into question. This involves, for example, attempting to open to continual question what I know, feel, do and want, and finding ways to engage actively in this questioning and process its stages. It involves seeking to monitor how what I do relates to what I espouse, and to review this explicitly, possibly in collaboration with others, if there seems to be a mismatch. It involves seeking to maintain curiosity, through inner and outer arcs of attention, about what is happening and what part I am playing in creating and sustaining patterns of action, interaction and non-action (p.155).

My research on my practice is very much contextual, abstract and imprecise but very real:

Through action research people can come to understand their social and educational practices more richly by locating their practices, as concretely and precisely as possible, in the particular material, social and historical circumstances within which their practices become accessible to reflection, discussion and reconstruction as products of past circumstances which are capable of being modified in and for present and future circumstances. While recognizing that every practice is transient and evanescent, and that it can only be conceptualized in the inevitably abstract (though comfortingly imprecise) terms that language provides, action researchers aim to understand their own particular practices as they emerge in their own particular circumstances, without reducing them to the ghostly status of the general, the abstract or the ideal -- or, perhaps one should say, the unreal (Kemmis & Wilkinson, 1998, p. 25).

Several excellent summaries of the literature in the field of action research can be found. One of these is Susan Noffke's chapter, "Professional, Personal, and Professional Dimensions of Action Research" (in Apple, M. (Ed.) (1997) Review of Research in Education, 22) with which I engage in the thesis. 4

The Appendix to Ben Cunningham's Ph.D. is a useful summary of the historical roots of action research, many research leaders in the field up to 1999 and the form of action research that the students of Jack Whitehead understand in answering the question, 'How do I improve my practice?' (Cunningham, 1999). A more recent publication, Geoff Mills' (2000) Action Research: A Guide for the Action Researcher is a useful guide for beginning teacher researchers although his use of "practical action research" (p.9) seems redundant since it seems to me that its essence is in the practice. Most especially, I and many others (June 27, 2001, 32,000 hits to the website) have referred to Jack Whitehead's Ph.D. thesis (Whitehead, 1999) and web page - http//:www.actionresearch.net - both of which have informed my research and writing. I want to establish that "justifying" (Mills, 2000) the choice of action research as a legitimate process may have been essential when I first started the research in 1996. I have seen the dramatic change in its acceptance at the American Educational Research Association (AERA) annual meeting over the last seven years. In 2002 in New Orleans, action research was on the agenda of many researchers. In several sessions that I attended, the rooms were full to overflowing with questions of the sort, "I have to teach a 10-week module on action research in my program. Can you help me?" as teacher educators from across the globe were distressed that they had been mandated to teach these modules with no experience.

What I do want to make clear is that the process that I am using is a particular approach to action research developed by Jack Whitehead (1989, 1993, 1999), a discipline of educational inquiry- "living educational theory". Ten Ph.D.'s at Bath University in the living theory section of Jack's website (and several others at Deakin, Exeter, Curtin, Kingston) provide testimony to the value of the process in contributing to the knowledge base of practitioner research.

Our perceptions of the world are based on a number of things from childhood experiences to schooling to job-related crises. One source of my perceptions of advanced academic research and writing was from conversations with colleagues. I would frequently hear that their professors/supervisors had given such specific direction that they felt they were no longer the author of their own work and felt no ownership or joy in their final projects or theses. I wondered what then was the point of the exercise? Phyllida Salmon explains the qualities that she believes the Ph.D. student must have: awareness of the personal significance of the work and that such work is transformative of the person carrying it out; ownership of the ideas expressed within it; creativity and vision to produce new meanings; intellectual courage to cope with the tentative and uncertain nature of such enquiry. She puts forward these ideas in direct opposition to a positivistic view of the Ph.D. as research training (Salmon, 1995, p. 9, 10 in Parker, 1998).

I am in agreement with the description of the action research process "as a messy series of false starts" by Ph.D. student, Mary Hanrahan (1998). "What may appear to some people as a messy series of false starts and changes in direction, now appears to me to be a rational progression in my ideas about the most appropriate goals and methodology for research in education." While I had my share of difficult times, I never felt as she did, being doubted by her supervisor and "that there was something wrong with me and my methods." In the end, though, I felt as she did that the research has led "to much personal growth for me and a new zest for life" (p. 305).

So when I came to do my own research and write my thesis, I knew intuitively that I would have to conduct the research and write the thesis in a way that made ontological sense to me and that reflected my ways of knowing and being. I knew without full understanding at the time that I was opposed to a purely scientific method of "gaining understanding of the world":

Academic knowledges are organized around the idea of disciplines and fields of knowledge. These are deeply implicated in each other and share genealogical foundations in various classical and Enlightenment philosophies. Most of the 'traditional' disciplines are grounded in cultural world views which are either antagonistic to other belief systems or have no methodology for dealing with other knowledge systems. Underpinning all of what is taught at universities is the belief in the concept of science as the all-embracing method for gaining an understanding of the world (Smith, 1999, p. 65).

I find action research to have a very spiritual as well as practical aspect much as Peter Reason describes in "Action Research As Spiritual Practice" (2000) and as Ben Cunningham lived in his thesis, How do I come to know my spirituality as I create my own living educational theory? (1999). I resonate with Jerry Allender (2001) as he describes why he chose self-study:

Objectivity is an obsessive concern in Western culture, and this obsession distracts from a larger worldview. Besides annoying encounters with narrow conceptions of objectivity in daily life, like academic committees paralyzed for lack of the right numbers, other experiences have been particularly troublesome for me as a teacher. My actions in the classroom, what I want education students to learn, and the research I do on the process of teaching have all been affected. More difficult yet, the emphasis on objectivity masks the power of self-knowledge... (p. 2).

To attempt to create a holistic picture of my learning and improvement as a superintendent of a large rural and semi-urban school district in Ontario, Canada, Grand Erie District School Board (GEDSB) over six years is to challenge traditional forms of data representation and research in educational administration. With this in mind, I wish to bring my voice into the knowledge base of educational leadership to respond to Beatty (2000): "Indeed, what is missing from the knowledge base for the emotions of leadership are the voices of leaders themselves" (p. 332).

What approaches did I use to conduct my research?

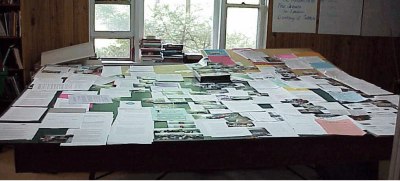

How can I transform the story of my learning through five years studying my practice that is visually and physically spread out in my recreation room on a huge table? What would it look like to show the meaning of the values I hold and transfer the documentation on the table to reveal my learning? How can I describe and explain my learning within my internal capacity and energy to sustain my own learning and to engage and support the learning of teachers and administrators for the purpose of enhancing student learning? Looking at the photos puts me in touch with my values: I am different people in different contexts with the values I hold as the unifying force. The story appears like rivulets running across the plain to converge into a river of knowing and theorizing about my life as a superintendent. In terms of my own learning the spider plant metaphor that Gareth Morgan (1988) uses may help to explain how I learn a skill or aspect of knowledge and teach others what I have learned. Once the other person has learned the skill, he/she becomes independent of the direct support as an autonomous individual. The list of my learning and teaching is long: the action research process, the use of digital still and video cameras, staff development and leadership, curriculum, assessment and special education and so on.

|

|

|

This table in my recreation room allowed me to see in visual form the processes and patterns of my learning over the 6 years. I had to add new surfaces as the papers data trail grew.

|

|

|

Much of my data collection, analysis, synthesis and writing concerns the role of the professional educator, my role as teacher and as learner. I am creating myself in a process of improvisatory self-realization (Winter, 1989) using the art of the dialectician, in which I hold together "in a process of question and answer, [my] capacities for analysis with [my] capacities for synthesis":

What I think distinguishes my work as a professional educator from other professionals such as architects, lawyers or doctors is that I work with the intention of helping learners to create themselves in a process of improvisatory self-realisation (Winter, 1998). Stressing the improvisatory nature of education draws attention to the impossibility of pre-specifying all the rules which give an individual's life in education its unique form. As individuals give a form to their lives there is an art in synthesizing their unique constellations of values, skills and understandings into an explanation for their own learning. I am thinking of the art of the dialectician described by Socrates in which individuals hold together, in a process of question and answer, their capacities for analysis with their capacities for synthesis (Whitehead, 1999).

In Peter Mellett's Review (2000), a clear description of my intention to "make a claim to knowledge and a claim to life" is articulated:

Writers associated with the academy, educational action researchers, and those from other arenas who comment on their endeavours, are all making claims from within their writing to have knowledge. My own claim is that the writers of good-quality educational action research accounts are making a claim to know their own form of life: I am suggesting that, through our practices and our texts, we are making a claim to knowledge and a claim to life. We link their own lives with the lives of others in order to bring about an improvement that is life-enhancing and life-affirming. We are showing how we strive to live out our values of freedom, democracy, and justice in our shared lives (p. 28).

As I describe this research process, I am reminded of Schön (1995) talking about the fact that "know-how is in the action" (p. 29) and that refers to acts of recognition and judgment as well as to physical skills. He refers to Polanyi's "tacit knowing" which is so difficult to define:

Michael Polanyi, for example, has written about our ability to recognize a face in a crowd. The experience of recognition can be immediate and holistic. We simply see, all of a sudden, the face of someone we know...Polanyi speaks of perceiving from these impressions to the qualities of the place. [This is] what Polanyi calls "tacit knowing" (p. 30).

I have been reminded frequently, particularly in the Validation Group responses in 1997, 1998, 2000 and 2001 that I need to describe and explain my actions and reflections deliberately because I experience them as inherent and need to make the implicit, explicit. Schön (1995) describes a situation where a piano teacher sees an error in a student's work but must play it herself in order to be able to help the student as a means to show that we need to see ourselves in action:

Often, we misstate what we know how to do. Indeed, when we ask people to describe what they know how to do, we are likely to get an answer that mainly reveals what they know about answering the question. If we want to discover what someone knows-in-action, we must put ourselves in a position to observe her in action. If we want to teach about our doing, then we need to observe ourselves in the doing, reflect on what we observe, describe it, and reflect on our description (p. 30).

The method of inquiry I have used has evolved over time but there are some constants from March of 1996. From the beginning I have had a concern for truth and being true to myself and my responsibilities, a preference for a visual forms and dialectical and dialogical processes and the requirement that the research help me improve (become a better superintendent) as I made an original contribution to the knowledge base by developing my own "living educational theory." (Whitehead, 1989). In my life and work I believe in collaboration. I hold the same belief in research. I have engaged many people, my children, colleagues, university academics, friends, strangers at conferences, formally and informally, by sharing, talking about, and requesting responses to my research. I have embraced many willing, caring collaborators.

During the years that I have been researching and writing, years of massive change in education, I have performed a demanding job, superintendent of schools, always striving to meet my own highest expectations and standards. And at the same time I have been an active single parent. There have been no study leaves or sabbaticals, only holidays, evenings and weekends. However, the advantage (or disadvantage) of experiential, reflection on and in action (Schön, 1983), self-study action research is that I live, eat and breathe the research. There is no separation from it; it pervades by life and work. Research of this kind "is often linked with the researcher's life process, as they pursue topics of personal relevance and hope to achieve life development as well as intellectual insight" (Marshall and Reason, 1987; Marshall, 1992 in Marshall, 1995, p. 24). I have "a personal stake and substantial emotional investment" (Anderson & Herr, 1999) in my project and I am "experience- near" (Geertz, 1983 in Anderson & Herr, 1999) to the work. Because I have engaged so many people in the process, I have also been teaching others the process as I have been learning it. It has been very symbiotic and synergistic.

I will elaborate on my approaches to the research. I have conducted my research through analysis and synthesis of an extensive data collection; writing, sharing and rewriting; learning through the writing process; giving the thesis a form; using photos and video in image-based research; emphasizing dialogic research and voice, and; becoming a practitioner-scholar. As I have conducted my research, my methodology has been one of 'meaning-making' from the data and my life.

Analysis and Synthesis of an Extensive Data Collection

The research database, which includes some quantitative but, primarily, qualitative data, is extensive. It includes journals expressed as e-mails, case studies, audio and videotapes, transcripts of meetings and interviews, meeting minutes, surveys, reports and policy and procedure documents, print, video and electronic publications - mine and others', film and digital photographs, and validation responses and meetings. Over the six years, I have kept journals, daily and often more than once a day, of my activities and reflections by means of e-mails to Jack Whitehead. This was part of the dialogical process. I also have records of e-mails to other academics and professionals that serve to show the progress of various directions in my work and life. I have found that I need an audience for my thoughts as well as a respondent.

Over several months late in 2000, I read and reviewed and sifted and reflected on my collection of data spread over an old pool table extended via other surfaces. Visiting and revisiting the data has been essential to understanding because it is "difficult for the action researcher to grasp everything at once and data may need to be revisited in the light of new experiences" (James, 1999) I re-read and reflected on my narratives of school board amalgamation, supporting action research projects, creating the masters program in partnership with Brock University, my published writings and validation papers, my performance evaluations and looked with new eyes at the hundreds of photos I'd taken over the six years.

My standards of practice and judgment emerged as I peeled back the layers while I turned my life in my mind and looked at new faces of the whole. I found that standards connected and overlapped and I allowed them to do so. For some time I deliberately avoided forcing a form on my theorizing, fearful that my need to control would limit the opportunity to learn more deeply through the process of writing, reflecting and re-writing. I have a firm belief in the value of learning as a transformatory process and of writing as a learning process. Laurel Richardson (1994) terms this, "writing as a method of enquiry, the process by which we come to knowing through our writing" (p. 4). I found that each piece of writing changed my knowledge and increased my capacity to theorize. As Van Manen (1988) says, "we are unable to do much more than partially describe what it is we know or do. We know more than we can say and will know even more after saying it" (James, 1999).

In describing and explaining my standards in February, 2001, (Delong, 2001a) 5

I included a number of vignettes that I intended to give life and vitality to my standards. Then and now, I wish most fervently to avoid the "linguistic checklists" (Delong & Whitehead, 1999) prevalent in the work of professional bodies like the Ontario College of Teachers and the (UK) Teacher Training Agency. And yet, I found myself initially presenting nothing less than a list of standards like posts in a fence. I found representing lived experience (VanManen, 1990) to be a messy process of improvisatory self-realization (Winter, 1997) challenging and less than satisfactory when what I had produced appeared to be clearly-defined but lifeless categories and lists of what I called 'my living standards.' There was a certain irony there. However, I realized in the three-week period that I was at the University of Bath in March 3-25, 2001 that the fifteen standards I had written in February needed further synthesis and evaluation. In this thesis you will see that transformation over the next twelve months where I have come to know them in two values that are my standards of practice and judgment.

Writing, Sharing and Rewriting

It seems to me that the written word is limited in its capacity to represent my life as an educator and "insider researcher" (Anderson & Herr, 1999; Anderson & Jones, 2000; Reihl et. al., 2000). Much has been written about the acceptability of alternative forms of data representation (Eisner, 1997); however, there appear to be few exemplars to follow. Certainly narrative, which "blurs the distinction between science and art" (Allender, 2001, p.2), is one useful form of representing my life that I use. I do find, however, that the printed word is limited both my capacity to creatively describe and explain and the limitations of the language to capture aesthetics, spirituality and emotion. Part of my challenge is to capture in a tangible form the passion I feel and the "life-affirming energy" (Bataille, 1962; Whitehead, 2000) I hold for education and educators.

George Bataille (1962) describes the limitations of language and the desire I share with many others to "understand the riddle of existence" and "seek the heights" while recognizing that:

This body of thought would clearly not be available to us if language had not made it explicit.

But if language is to formulate it, this can take place only in successive phases worked out in the dimension of time. We can never hope to attain a global view in one single supreme instant; language chops it into its component parts and connects them up into a coherent explanation. The analytic presentation makes it impossible for the successive stages to coalesce.

So language scatters the totality of all that touches us most closely even while it arranges it in order. Through language we can never grasp what matters to us, for it eludes us in the form of interdependent propositions, and no central whole to which each of these can be referred ever appears. Our attention remains fixed on this whole but we can never see it in the full light of day. A succession of propositions flickering off and on merely hides it from our gaze, and we are powerless to alter this.

Most men are indifferent to this problem (p.274 -275).

Given its limitations and recognizing that it is still the primary mode of sharing knowledge, I have combined written language with image-based research (Mitchell & Weber, 1999; Prosser, 1998; Schratz, 2001; Walker, 1993). Recognizing the limitations of language is important but also important to me is my learning through the writing process.

Learning through the writing process

One of the "ah ha's" of researching my practice and of teaching others the process has been the significance of writing for reflection and learning. Now you would think that a person with an undergraduate degree in English who taught the subject to high school students for eight years (1966-72; 1980-82) would already know this. Perhaps I did as "tacit knowledge" (Polanyi, 1958), but not to the depth that I now know it. In a thoroughly enjoyable book that I used in teaching the masters Narratives Course 6

, The Right To Write, Julia Cameron (1998) talks about the nature of writing:

Although we tend to think of it as linear, writing is a profoundly visual art. Even if we are writing about internal experience, we use images to do it and about the need to write:

- We should write because it is human nature to write.

- Writing claims our world.

- It makes it directly and specifically our own.

- We should write because humans are spiritual beings and

- writing is a powerful form of prayer and meditation,

- connecting us both to our own insights and

- to a higher and deeper level of inner guidance.

- We should write because writing brings clarity and passion to the act of living.

- Writing is sensual, experiential, grounding.

- We should write because writing is good for the soul.

- We should write because writing yields us a body of work,

- a felt path through the world we live in.

- We should write, above all, because we are writers,

- whether we call ourselves that or not.

(p. 55, 56).

This writing about myself is intensely personal. I feel vulnerable but not at risk. I have not intended to make any of the people I have included in the writing uncomfortable or at risk. I have checked back many times to ensure that I have been ethical and fair. After reading Chapter One which is about him, Peter Moffatt wrote back to me: "Thanks. I enjoyed and learned from reading the last two sections. You have used your reflective mode to make sense and find satisfaction in work." (handwritten note,15/08/01) The narrative has been written with love and with a sincere desire to understand and improve my own practice and to explain the life of an educational leader with clarity. Cameron (1998) likens this to the act of singing:

In the practice of singing, much can be done with technique. There is, however, an elusive something that comes when the singer "sings with love." That intention brings to the voice a purity that is at once evanescent and unmistakable. The same purification happens to our writing when we write with loving intent. It is a great paradox that the more personal, focused, and specific your writing becomes, the more universally it communicates (p. 54).

In my work whether it be delegating a task to someone or committing to the process of accomplishing a task through a committee or project management team, I have to trust the process. I have frequently advised groups who are undertaking practitioner research to just let the action-reflection process, the journalling and dialogue with critical friends, and the writing and sharing happen, to trust the process. Amazing how difficult it is to take your own advice! I now know that I can trust the process. The actual writing, reflecting, dialoguing, revising, and revising again, has created my knowing. At the beginning of writing, I had masses of research data, a messy rummage of thoughts and ideas, confusion and chaos, and an excruciating need for order and clarity.

You would laugh if you could see the family/recreation room that I converted to a writing centre for the writing of this thesis. See the photo above. There is no order or clarity here. The reason it works for me is that I am a holistic thinker and need the picture of the whole before I can deal with the pieces. It is one of the reasons I struggled with the learning of math in high school from very sequential teachers. I was thirty-five years old and an occasional teacher teaching classes of business math when I realized this. So having chart paper on the walls with timelines and themes and all my research data, books, publications and photos spread out visibly was an essential environment for me to write. Only then could I start the integration:

Writing is a valuable tool for integration. The root of the word "integration' is the smaller word "integer," which means "whole." Too often, racing through life, we become the "hole," not the "whole." We become an unexamined mass into which our encounters and experiences rush unassimilated, leaving us both full and unsatisfied because nothing has been digested and taken in.

In order to "integrate" our experiences, we must take them into account against the broader canvas of our life. We must slow down and recognize when currents of change, like movements in a symphony, are moving through us (Cameron, 1998, p.107-108).

I wrote the thesis the same way that I live and work - with intensity. With the exception of short breaks such as walks, conversations with my friends and children, I usually wrote for eight to ten hours a day, weekends and holidays. I found an hour here and there was not productive. Because of the random nature of my thinking processes (Delong & Wideman, 1996), I usually worked on three or four documents on the computer screen at once plus the references page and the parking lot, and pulled a new one up as I found a connection to another. I would move back and forth between my data, the literature, thinking, writing, and revising. I place great importance on connections and patterns and wish to connect my life and research with you in the spirit of Gregory Bateson (1980):

In every instance, the primary question I shall ask will concern the bonus of understanding which the combination of information affords. The reader is, however, reminded that behind the simple, superficial question there is partly concealed the deeper and perhaps mystical question, "Does the study of this particular case, in which an insight develops from the comparison of sources, throw any light on how the universe is integrated?" My method of procedure will be to ask about the immediate bonus in each case, but my ultimate goal is an inquiry into the larger pattern which connects (p. 73).

I did not separate the literature search into a separate compartment as in the traditional academic search but engaged with the academic research as it came into the subject of the writing or triggered some critical judgments in my data analysis, synthesis and evaluation:

The good news is that the Handbook of Research on Teaching, edited by Richardson (1998) does have a chapter dedicated to practitioner research, albeit written by academics. Zeichner and Noffke (1998), the authors of the chapter, suggest that it may be premature and perhaps inappropriate to engage in the academic style literature reviews of teacher research. Instead they argue that research done by teachers should not be seen as merely an extension of the current knowledge base but rather a challenge to existing forms of knowledge (Anderson & Herr, 1999, p. 13).

My train of thought being what it is, more like a moving target than a straight line, I kept a section at the end of each document called "Parking Lot". As a new idea, memory, image, or connection would wash though my mind, I would "park" it in the parking lot and come back to it later. This process was similar to what Ron Wideman and I came up with as we worked on the book Action Research: School Improvement Through Research-Based Professionalism (1998b), only in that case to retain my random thoughts and to keep us on task I used post-it notes stuck on the table. This process of parking an idea or process is reflected in my life. When a project is not working, I park it until the constellation of factors that will make it come together emerge.

|

|

|

On March 13, 2001, in Jack’s office I printed out my writing over the six years of research and forced them into a purple binder. It was a cathartic event because it had a form, a very imperfect one but at least a form.

|

|

|

Giving the thesis a form

The final throes of creating a thesis out of a mishmash collection of writing began with the writing and rewriting of my abstract on March 8, 11 and 12, 2001. When I presented it to the Bath Action Research Group on March 12, Robin Pound, one of the researchers in the group from the nursing field, felt that there was something missing and wanted to include some of my learning while Sarah Fletcher, lecturer and Ph.D student at Bath, said that she thought the "Wow" was missing. Jean McNiff said that the abstract was elegant and exciting and that if I could write the thesis that the abstract described, she would like to read it. Just a little challenge! Jack wondered if it needed a photo. I redrafted it on the March 20th. This process was described and explained in our AERA paper presentation (Whitehead & Delong, 2001). 7

On March 9, 2001, I drafted a structure for the thesis with possible chapters, which was redrafted many times over the next four months. On March 13, I printed off the writings that I had produced in the six years of the research, organized them into the chapters I had proposed. It was an ugly, overstuffed binder of papers but at least now I could see a whole: a behemoth challenging me to make it aesthetically pleasing. Stephen Taylor's (2001) paper, "'That Was Ugly'": Assessing Organizational Aesthetic Performance", made a connection. However, I began to see a flow because as I was organizing, I was writing Chapter Four which I had named 'My Learnings' which is now integrated into several chapters in the thesis. There was a flow back and forth of reading, reflecting, synthesizing and writing.

Then I started on a Table of Contents page of what the reader could expect to come across in the thesis. I needed to make connections for the reader so that he/she could move back and forth in time in each of the areas of the work and my learning. It needed a means for the reader to make the connections. I came upon the idea of footnotes as connectors.

As I wrote I could sense the emerging theorizing about my life as an educational leader. There was an emerging knowing that had not been there before the writing. The writing process mirrored my life and how I manage to keep multiple tasks and levels of activity held together, how I organize my life as a superintendent by integrating the personal and professional, and how I manage to live out my values within a political and economic system of education in complex and tumultuous times. Some examples of my writings can be found in Part A of the Appendices.

Photos and video in image-based research

Photos are powerful for filling out and adding feeling and enhanced complexity to the written description of an event. When the only person in my first validation group meeting, February, 1997, who understood my job from my description in the paper, (Delong, 1997a) was Peter Moffatt, the Director of Education 8

(who had been a superintendent in the same district himself), I attributed the problem to my incapacity to communicate my role to my inadequate writing skills. Over the subsequent years I have come to realize that images, whether metaphors, graphs, visuals, drawings, or photos, are essential to my clarity of thinking and writing. They also provide a support that enhances the written word and may address the concern of Bataille's (1962) that "through language we can never grasp what matters to us" (p. 274).

I have been very specific in this title because I recognized the concern of Walker (2001) around the word 'image': "The use of the word 'Picture' rather than 'image' is intentional. You could fill a library with books that have the word image in the title, but contain no pictures" (p. 1). I will be referring to photos and videos in my language of image-based research and will be including them in the thesis, bearing in mind Jon Prosser's (1998) view that they play "a relatively minor role in qualitative research" (p. 97). They are significant in my research.

Throughout the research, I have struggled with the problem of representation. During a January 20, 2001 overseas telephone conversation with Jack Whitehead, I decided to see if integrating a few of the many photographs from my research would assist in giving life to my standards. I had inserted them with considerable difficulty into my December 5, 1997 response to the research committee at Bath. For me, photos are a powerful way of relating to individuals. That simple act (I use the word 'simple' loosely because learning the process of inserting them into the text was not 'simple' and at one point actually crashed a computer) transformed my thinking and writing because when I am working, thinking or planning, I am holding people in mind. "The value of the single photograph lies in its potential to help uncover layers of meaning" (Mitchell & Weber, 1999, p.101). I find that the photo or "vernacular portrait" (Mitchell & Weber, 1999, p.77) links the image to the person with an immediacy that helps me sustain the feeling or thought. It is inherent in my standard of valuing the other and a means to create a link to another person with a permanent record. Photographs enable me to make connections with and among people and events, both within my research and my life. The use of video goes even further in explaining my life as you will see in Jack's website www.actionresearch.net. As Mitchell and Weber (1999) point out that:

|

|

|

Jack Whitehead, my Ph.D supervisor, and I in dialogue about creating my thesis on August 1, 2001. Note the videocamera in the foreground. We frequently taped our dialogue in order to trace the process of my developing methodology.

|

|

|

...images and sound and movement over time...yields a self-representation that is different from the still photo, one that appears more fluid than frozen, confronting us, not with a single slice or drop we can put aside under the microscope and decontextualize at our leisure, but rather with a running stream that presents multiple examples, variations, and complexities--perhaps even contradictions and tensions. In comparison with a photograph, video is a more complete and noisy text...Viewing this self-representation may problematize the way we think of ourselves, challenging our idealistic mental snapshots. But it can also reassure us, providing a wider sampling of images and behaviour from which to choose the ones that we feel 'capture' us (p. 193).

I have collected and analyzed some more "fluid than frozen" (Mitchell & Weber, 1999, p. 193) video clips on CD-ROM in my data archive and have used them frequently in presentations (Whitehead & Delong 2001a).

I was interested in the work of Walker and Schratz presented at the Second Annual CARE Conference Applied Social Research: Method and Practice on 23-23 July 2001 at the University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK on image-based research. I am in agreement with Walker (2001) that photos put the researcher in the work. "Often in the narratives that you encounter in research, the author remains 'above' the text, looking down (just as a geographer's gaze is typically that of the bird's eye view)" (p. 9).

The meanings that the photos carry go beyond the first impression since "they connect to other places, other projects and other sets of meanings" (Walker, 2001, 13) and carry meanings of great import to the understanding of the writing and their use "touches on the limitations of language, especially language used for descriptive purposes. In using photographs the potential exists, however elusive the achievement, to find ways of thinking about social life that escapes the traps set by language" (Walker, 1993, 72 in Schratz, M., 2001, 4). I feel as Walker does that "looking at the photographs creates a tension between the image and the picture, between what one expects to observe and what one actually sees. Therefore, images 'are not just adjuncts to print, but carry cultural traffic on their own account'" (Walker, 1993, 91). He also wanted to use the photograph in order to "find a silent voice for the researcher" (Walker, 1993, 91 in Schratz, M., 2001, 4). Michael Schratz shares his and Walker's thoughts on the use of pictures in research:

"Despite an enormous research literature that argues the contrary, researchers have trusted words (especially their own) as much as they have mistrusted pictures." (1995, 72) For them the use of pictures in research raises the continuing question of the relationship between public and private knowledge and the role of research in tracing and transgressing this boundary. "In social research pictures have the capacity to short circuit the insulation between action and interpretation, between practice and theory, perhaps because they provide a somewhat less sharply sensitive instrument that works and certainly because we treat them less defensively. Our use of language, because it is so close to who we are, is surrounded by layers of defense, by false signals, pre-emptive attack, counteractive responses, imitation, parodies, blinds and double blinds so that most of the time we confuse others and even (perhaps, especially) ourselves" (Schratz and Walker, 1995, 76) (Schratz, 2001, 3-4).

|

|

|

On April 6, 1998, I was launching the Action Research Kit and thought I was hiding my unhappiness at the prospective loss of my job but despite the pleasure I felt in the work we’d done in the kit, my presence was not happy.

|

|

|

Photos have great depth of meaning for me and seeing them evokes memories, emotions and thoughts. You will note that the photos are of people, not events. The people in the photos are part of my life and my research and they want to be included. I would not be able to create this thesis without the people in the photos in mind. They also reveal facts of which I had been unaware. An example is the obvious strain that I was experiencing at the time of the launch of the Action Research Kit, 9

a strain that I thought I was successfully hiding from the world. The photos revealed the truth. "According to Susan Sontag (1979, 88) photos are not only evidence of what an individual sees, not just documents but an evaluation of the world (view). They present a "vision" of the relationship between subjects and objects, which manifests itself in the snapshot" (Schratz, 2001, 18).

The visual representation became increasingly important in my research because taking and sharing photos was part of my living my life and I found that including them in my writing provided a means for me to understand my life and work and to communicate that to my audience. I use the sharing of them as well as a means to connect with people and build relationships. Most people I know like to get copies of photos to remember events and places and I consistently do that, always a camera in hand and getting and sharing extra copies of photos.

In order to communicate as clearly as I can "in the full light of day" (Bataille, 1962, p. 275), I use still photos and where possible video-clips to enhance the capacity of the words. The voices of the people in transcribed conversations, interviews and reports who have lived with me through these years of my research add depth and strength to my own voice as I explain my embodied knowledge. On the cover of Ben Okri's Birds of Heaven (1996) is the reminder:

We began before words

And we will end beyond them.

Dialogic research and voice

In this thesis I wish clearly to emphasize the role of dialogue in my learning to improve and my commitment to retaining the integrity of my own voice as a practitioner and to encouraging other practitioner-researchers to share their learning with their own voices. I intend that my work and that of the researchers that I have encouraged and supported will strengthen the evidential base necessary to create that body of knowledge base of teaching and learning theory from the location of practice.

One of the things that I learned about myself in the process of researching my practice was that I extend my learning by thinking out loud, in dialogue with others. Being that I conducted most of my research over three thousand kilometers away from the university and my supervisor and with no study group, I was dependent on e-mail for dialogue. The first problem was to get connected via internet e-mail. The story from the inception of the process on February 22, 1995 at the Act Reflect Revise Conference in Toronto to the writing of the thesis is one of frustration in learning to make the technology work. In fact the evidence of that frustration recurs repeatedly in the e-mails through the entire process of the study. Jack had visions of our using the videoconferencing capacities to talk but despite many attempts with various software, it is only as I am finishing my writing of the thesis that we actually finally connected on August 24, 2001. It was a happy event. At least we reached that goal.

David Coulter (1999) argues for dialogic research in his article in the April 1999 issue of Educational Researcher and uses the work of Bakhtin (1895-1975) as the basis for his proposal that dialogue can improve research and its application to practice. "Bakhtin offers some criteria to use in thinking about how truth is made between speakers in dialogue" (p. 5). He also cites Maxine Greene (1994) for a conception of research as dialogue in which:

[w]hat matters is an affirmation of a social world accepting of tension and conflict. What matters is an affirmation of energy and the passion of reflection in a renewed hope of common action, of face-to-face encounters among friends and strangers, striving for meaning, striving to understand. What matters is a quest for new ways of living together, of generating more and more incisive and inclusive dialogues (p. 459).

Coulter (1999) says that Bakhtin's overriding concern with dialogue is that it is not simply verbal interchange, but the

single adequate form for verbally expressing authentic human life...Life by its very nature is dialogic. To live means to participate in a dialogue: to ask questions, to heed, to respond, to agree, and so forth. In this dialogue a person participates wholly and throughout his whole life (Bakhtin, 1963/1984a, p. 293) (p. 5).

According to Coutler (1999), Bakhtin "distinguishes between two kinds of meaning [in language]: the abstract or dictionary meaning and the contextual meaning...Language is never a unified system, never complete. Instead it reflects the complexity and unsystematic messiness of experience. Language can be unified when life is unified." (p. 6).

While one of my purposes in writing this thesis is to find my own voice, I have an innate need to share my learning and to support others to find their voices by: "finding the voices silenced or marginalized by monolithic practices"(Coutler, 1999, p. 9). As I supported Greg's and Cheryl's 10

research and writing and as I wrote with them, I encouraged them to share their hopes and fears and learning and growth to support others to give voice to their professional lives. Many of the voices of practitioner-researchers that I have had a hand in supporting can be found in The Action Research Kit (Delong & Wideman, 1998a,b,c), The Ontario Action Researcher (OAR) (Delong & Wideman, 1998-2002) http://www.nipissingu.ca/oar, in An Action Research Approach To Improving Student Learning Using Provincial Test Results (Wideman, Delong, Hallett & Morgan, 2000), Passion In Professional Practice: Action Research in Grand Erie (Delong, 2001), in board reports and in provincial and local conferences. 11

Becoming a practitioner-scholar

It has been a demanding path to feeling confident in my knowing and knowledge and to feeling that I am a scholar. Through much of the period of research I questioned that capacity and needed much support and affirmation. So why did I need the affirmation? There are several reasons. Unlike the masters' cohort, I have no peer group with whom to share ideas. Amongst my colleagues, no other superintendent is researching his/her practice; in fact, some take offense at it and only Peter Moffatt 12

even wants to hear about my research. Thank goodness for him. Second, I don't see myself as an academic, an intellectual. Third, I have read and listened to enough criticisms of qualitative and action research that I think it undermines my confidence that my research, my knowing, my epistemology is accepted as valid. And last, of the several proposals that I have submitted to the Administration Division of AERA, only the ones that I have submitted with Jack have been accepted. Despite what seem to both Jack and I to be quality proposals, when I submit on my own they are not accepted. I guess practitioner research still has a way to go to acceptance. I do not want to leave this point without saying that I have already made plans to try again for 2003.

Having said that, I want them to be wrong about my work and my research. Gary Anderson and Kathryn Herr (1999) in Educational Researcher gave me hope in their article, "The New Paradigm Wars: Is There Room for Rigorous Practitioner Knowledge in Schools and Universities?" I hope, of course, that the answer to their question is a resounding "Yes". And through my own "battle of snails", I want to help create that room for other practitioners. They cite Donald Schön (1995):

It is a battle of snails, proceeding so slowly that you have to look very carefully in order to see it going on. But it is happening nonetheless.

According to Schon (1995) "the new scholarship" implies "a kind of action research with norms of its own, which will conflict with the norms of technical rationality-the prevailing epistemology built into the research universities" (p. 27). ... Nevertheless, we believe that the insider status of the researcher, the centrality of action, the requirement of spiraling self-reflection on action, and the intimate, dialectical relationship of research to practice, all make practitioner research alien (and often suspect) to researchers who work out of Gage's three academic paradigms.

Certain epistemological stances will be more of a threat to institutions than others will, and institutional structures and politics will, to some extent, determine the epistemological stances that can be safely advanced (p. 12).

The successful partnership with Brock University in the masters program gives me hope, too. I feel that we are creating some of that "room" that Anderson and Herr (1999) talk about:

The problems faced by professional schools such as colleges of education are complex, since members of these communities must legitimate themselves to an environment which includes both a university culture that values basic research and theoretical knowledge and a professional culture of schooling that values applied research and narrative knowledge. (Meyer & Rowan, 1977). Viewed by universities as lacking in intellectual rigor, colleges of education are, at the same time, often viewed by school practitioners as too theoretical and "out of touch." Colleges of education have never walked this tightrope well, but the current crisis in teacher and administrator preparation, in which school districts are increasingly taking over the traditional functions of colleges of education, has forced the issue as never before (p. 12).

To describe the "battle" between the traditional forms of research and the practitioner research, Anderson and Herr draw from Schön's concern about the adoption of technical rationality by colleges of education as disqualifying action research processes:

This view of professional practice undergirds much of the epistemological debate that marginalized naturalistic/qualitative inquiry as 'nonempirical' prior to the 1970's and continues to largely ignore practitioner knowledge.

The coattails of legitimacy of qualitative research in the academy do not appear to be long enough to carry along action research done by school practitioners (p.13).

I think that is one of the barriers to the acceptance of practitioner research by the academic community and to my unwillingness for many years to engage in an advanced academic degree. Had it not been for Jack, I still wouldn't have. There is little in education (even budgets are values-based) that is divorced from "a personal stake and substantial emotional investment" (Anderson & Herr, 1999, p. 13). I can't do my job or my research without substantial emotional investment.

While Anderson and Herr (1999) feel that we are poised on the threshold of an outpouring of practitioner inquiry that will force important re-definitions of what "counts" as research, they recognize the restrictions that exist to having "schools as centers of critical inquiry in which teachers produce knowledge as they intervene in complex and difficult educational situations"(p. 14).

I take issue with their thinking that administrators and staff developers see teacher research as "the new silver bullet of school reform" (Anderson & Herr, 1999, p.14). In my work in Ontario and Quebec, I have not seen that. A relatively small number are even aware of practitioner research and where they are, it is seen as an option and given little sustained support. I know of only one school district where it has been mandated as a means to access certain Ministry of Education dollars for computer technology. I do have evidence that where teachers adopt the process of action research, they take control of their learning and become true professionals 13

(Wideman et al, 2000; Delong & Wideman, 1996, 1998a,b,c, 1998-2002; Delong, 2001b; Squire & Barkans, 1999).

There is still a defining line that prevents me, and many practitioners, from seeing themselves as part of the academic community. Part of this is that our knowledge is seen as practical and inferior and not formal and therefore, not real knowledge:

For many academics, the acceptance of practitioner research is given only on condition that a separate category of knowledge be created for it. This is usually expressed as some variation on "Formal (created in universities) knowledge" versus "practical (created in schools) knowledge," and a strict separation of research from practice (Fenstermacher, 1994; Hammack, 1997; Huberman, 1996; Richardson, 1994; Wong, 1995a, 1995b) (Anderson & Herr, 1999, p. 15).

Fortunately, some inclusive academics like Whitehead, McNiff, Lomax, Russell, Cochran-Smith and Lytle, Clandinin and Connelly, Ghaye and Ghaye are determined to change a restrictive, exclusive and limiting view of academia to embrace and encourage practitioner research as real knowledge. They see that "the concept of teacher as researcher can interrupt traditional views about the relationships of knowledge and practice and the roles of teachers in educational change, blurring the boundaries between teachers and researchers, knowers and doers, and experts and novices. It can also provide ways to link teaching and curriculum to wider political and social issues" (Cochrane-Smith & Lytle, 1999a, p. 22).

As I cite the work of Cochran-Smith & Lytle and Clandinin and Connelly, I recognize that the reference to "practitioner" means "teacher" and not primarily "administrator". In the notes (p.22) to the Cochran-Smith & Lytle (1999a) article, there is no reference to administrator. Clandinin and Connelly (1995) further divorce that connection by assigning administrators like myself the role of "conduit". Before I leave this section on becoming a practitioner-scholar, I need to say that I hope that my work and research put into question the negative view of the administrator as "conduit":

Researchers, policy-makers, senior administrators and others, using various implementation strategies, push research findings, policy statements, plans, improvement schemes and so on down what we call the conduit into this out-of-classroom place on the professional knowledge landscape (Connelly & Clandinin, 1999a, p. 2).

Throughout the book, the authors present a view that while they regret that they don't have the stories written by administrators, they paint program consultants, senior administrators and trustees with negative and harmful actions through being "the conduit" of processes such as implementation strategies. A missing piece in their work is the understanding of systems, political actions, market influences, mandatory legislation and other internal and external influences which impact on decisions made to keep a system of schools afloat and productive in improving student learning. It also assumes that leaders simply pass policies on without thought or supports. That has not been my experience. 14

I feel that I am responding to the call for "insider" research by administrators, for collaborative efforts by school boards and universities and for the creation of a dissertation that will be an account of "ways administrators modify traditional methods to engage in research at their own sites" (Anderson & Jones, 2000, p.20). I embrace the inherent challenges of insider research and like Marshall (1995), "I see research as 'a distinctly human process through which researchers make knowledge' " (Morgan, 1983, p.7 in Marshall, p.25). I have tried not to take personally the criticism that has been lodged at me both by peers and other staff. Insider research has its inherent risks. I have managed to overcome the black days when it appeared that I would not bring the study to successful completion. Because it is a human process, my story, like my life, is imperfect, inconsistent, full of tensions and far from clear. I have tried to make the writing transparent.

I do not wish to exaggerate the pressure of researching in my own system but I do want to make sure that I don't understate it:

Patricia Hill Collins refers to "the outsider within' positioning of research. Sometimes when in the community ('in the field') or when sitting in on research meetings it can feel like inside-out/outside-in research. More often, however, I think that indigenous research is not quite as simple as it looks, nor as complex as it feels" (Smith, 1999, p. 5).

As I felt when Lynne Hannay (1999) presented her research on action research in Brant 15

and when the research on superintendents was presented at AERA in 1997, I share Linda T. Smith's (1999) view that:

...the objects of research do not have a voice and do not contribute to research or science. In fact, the logic of the argument would suggest that it is simply impossible, ridiculous even, to suggest that the object of research can contribute to anything. An object has no life force, no humanity, no spirit of its own, so therefore 'it' cannot make an active contribution. This perspective is not deliberately insensitive; it is simply that the rules did not allow such a thought to enter the scene (p. 61).

I feel that writing my own insider story gives me a voice denied when others tell about the life of a superintendent.

However, having that voice does not mean that I have felt liberated to speak without constraint. In fact, I have probably been more careful about talking about my knowledge for fear of causing discomfort and as Peter Moffatt said at the February 17, 2000 Validation Group meeting, "Jackie has smoothed out some of the bumps." There is good reason for that.

Sometimes epistemological dilemmas blur into political dilemmas since, as Foucault has argued, knowledge and power are intimately interwoven (Anderson and Grinberg, 1998). Because administrators exist within a force field of power relations a major threat to validity or trustworthiness of administrator research is the nature of the administrator role itself Anderson & Jones, 2000).

Because I have had the support of Peter Moffatt and have consulted with him as to the sensitivity of my research, I have been able to "tell the truth" (Anderson & Jones, 2000) with full awareness of risk so that I have maintained a "trustworthiness".

Insiders have to live with the consequences of their processes on a day-to-day basis for ever more, and so do their families and communities. For this reason insider researchers need to build particular sorts of research-based support systems and relationships with their communities. They have to be skilled at defining clear research goals and 'lines of relating' which are specific to the project and somewhat different from their own family networks. Insider researchers also need to define closure and have skills to say 'no' and the skills to say 'continue' (Smith, L. T., 1999, 137).

Let me say that finding that closure to becoming a practitioner-scholar has been one of the most difficult aspects of my research. I am simply reporting on progress to date. The becoming continues.

How have I validated my claims to know?

When I submitted my transfer paper (Delong, 1997a), I said that I would be using my values, the work of others and the Ontario College of Teachers' (OCT, 1998) draft standards as my criteria for judging the quality of my work. I find that my own standards of judgment are revealing themselves as I explain my life and the various parts of my job. Validity questions are often thorny ones and, much like the OCT Standards of Practice, validity criteria need to sustain a fluidity and flexibility about them so that they are useful to the individual practitioner. Rigid checklists that create restrictive moulds will certainly limit the capacity of action research to capture the dynamic reality which is the life of a professional educator. Cheryl and I did try to conform to those standards 16

and in the process of applying them to ourselves, we recognized how much we were acting in violation of our values (Delong & Whitehead, 1998). I no longer wish to use the OCT Standards of Practice as validation criteria except to remind myself that standards of practice must be continuously regenerated and spontaneous.

To ensure validity in this work and to demonstrate originality of mind and critical judgment, I have used a variety of validation processes using my own values as standards of judgment. I am validating my knowledge through the description and explanation of my embodied knowledge, the voices of the people in my life, engaging with the voices from the literature, external assessment, established academic criteria and public presentation and accountability.

The description and explanation of my embodied knowledge

First, I would say that my personal practical knowledge, informed by the description, explanation and synthesis of the dialogical and dialectical processes that I have used to research my practice over six years, is embodied in my data collection. I am using Polanyi's (1957) position of my "being conscious of having taken the decision to understand the world from [my own] point of view", as one means of validation:

As action researchers we each ground our epistemology in our own personal knowledge and theorize from that standpoint, each 'I' being conscious of having taken the decision to understand the world from his or her own point of view, as a person claiming originality and exercising personal judgement responsibly and with universal intent (Polanyi 1957). My dual aim in writing this text has been for it to be acceptable from the point of view of current accepted standards of scholarship whilst, at the same time, giving a flavour of where a new scholarship (Schön 1995, ibid) that embraces personal knowledge might lead (Mellett, P., 2000, p.29).

The voices of the people in my life

Second, the voices of the people in my personal and professional life that have worked collaboratively with me, at times as co-researchers, provide evidence to substantiate my claims. I have known much pleasure in the development of the case studies 17

of Cheryl, a teacher, and Greg, a principal, as I shared the stories with them as they were written. With each new version, we talked at length and their reflections and responses informed and enriched the next version. This collaborative and iterative process has deepened my understanding of my influence and my relationship with each of them and with others.

These stories, indeed this thesis, is the story, "restoried" (Connelly & Clandinin, 1999) many times in my life history, focused on these last six years, during the chaos created by economic rationalist policies. I recognize that "there is no one true story; there are many possible tellings" (Denzin, 1989; Mann, 1992 in Marshall, 1995). While they are my stories, I have endeavoured to include the voices of others that have influenced me, taught me and encouraged me to tell this story of my life as a superintendent, a story of a superintendent who is more than a "data gatherer" (Anderson & Jones, 2000). To bring the reader into an understanding of the nature of my world, I have described the context, the landscape (Connelly & Clandinin, 1999), in as much detail and with as much actual conversation as I felt necessary. I have included, as well, photographs of people and events that may help to fill in the colours of the landscape. The visual and the dialogic permeate the story. People and relationships are the focal point of this, my educational landscape. The connections and relationships supported by a culture of inquiry, reflection and scholarship are essential to improving student learning, to the education of students. Herein lies my role as an educational leader.

Because of the dialogic nature of this study, critical friends and colleagues have played a significant role in testing and providing evidence to substantiate my claims to knowing. And, of course, Jack Whitehead stands, ever-vigilant, hand outreached, demanding, "What evidence do you have that anything you have done has helped any student, anywhere?" It may be that the 'plausibility' around that embodied knowing comes from the intense conversations in which I engage with Jack. It certainly includes conversations found in e-mails, transcriptions of audiotapes, reports, videotapes, CD-ROMs and performance reviews (Moffatt, 1995-2001a 18

; Berry, 1995-1997; Quigg, 1998-2000; Mills, (2001).

The voices from the literature

The available academic literature in the field has both informed and denied my learning. What I mean by this is that it denies my learning in the sense that my learning is practical and dialogical. I find an inability in the propositional forms to explain my life and they appear to deny the experiential meanings in my practice. Where the literature has validated my epistemology, I have recognized that valued support and challenge. Where it has denied my practitioner's knowledge, " 'I' being conscious of having taken the decision to understand the world from his or her own point of view, as a person claiming originality and exercising personal judgement responsibly and with universal intent" (Polanyi 1957 in Mellett, P. 2000), I have confronted that challenge with my own way of knowing (Belenky et. al, 1997).